exhibition staging and architecture

Carlo Scarpa, la Galleria delle Sculture a Castelvecchio, Verona

Carlo Scarpa è stato forse il più grande e insuperato maestro nella ‘messa in scena’ delle opere d’arte, trovando il luogo, l’orientamento, la luce, le condizioni di visibilità più appropriate per ogni singolo pezzo. Ma è stato maestro anche nella regia dei percorsi per il visitatore, nella composizione di contesti, di sfondi, di riscontri.

Non è possibile qui dar conto della sua straordinaria opera di allestitore in modo esauriente.

Abbiamo già visto alcune sale di Palazzo Abatellis (link) a Palermo (1953-1954). Possiamo ritrovare la sua magia di grande seduttore anche in un altro dei suoi capolavori, il Museo di Castelvecchio a Verona (1958-1975).

…

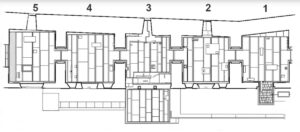

Al piano terreno di Castelvecchio, passata la biglietteria, il visitatore gira a sinistra e -salito uno scalino che marca la soglia- si affaccia sull’infilata delle cinque sale della Galleria delle Sculture (7.1).

Cinque sale nelle quali sono soprattutto la calce e il cemento in declinazioni diverse ad offrire la materia che fa da sfondo alle sculture: chiare pareti di ruvida calce grezza perimetrano pavimenti in piastre di grigio cemento bucciardato (7.3).

Su queste sono saldamente posati basamenti di cemento levigato o di acciaio, o, al contrario, sembrano levitare -come tappeti volanti- pedane nere di calce lucidata a specchio.

Fermandosi per un attimo sulla soglia della seconda sala, il visitatore -se non è mai stato a Palazzo Abatellis- scopre una stranezza: una statua gli volge la schiena. Poi, girando lo sguardo, prende atto che nessuna delle sculture è rivolta verso di lui -verso l’ingresso-, ché anche l’unica figura posta frontalmente -sulla parete di fondo- guarda altrove (7.2).

Allora, dopo aver osservato il panneggio che cade dalle spalle della statua, incuriosito, istintivamente il visitatore avanza e, come di fronte a persone vere che gli vengano presentate, cerca di vederne i volti.

Andando avanti, probabilmente si ferma e guarda a destra, per studiare la coppia di statue la cui pedana -attenzione!- ingombra il percorso centrale (7.4).

Da questa nuova posizione, la statua che era di spalle ora gli appare di tre quarti. Dunque avanza ancora, e le gira intorno.

Finalmente la vede davanti (7.5). Dagli strumenti musicali che porta con sé può comprendere che è Santa Cecilia. La osserva ancora bene, e poi, inevitabilmente, la confronta con quella sulla parete di fondo, di fianco all’ingresso, anch’essa ora orientata frontalmente.

E’ ora chiaro che l’apparente stranezza ha ottime ragioni.

Senza frecce o cartelli, Scarpa induce -quasi costringe- il visitatore a lasciare il percorso centrale, prima scansando la pedana con la coppia di statue, poi girando intorno a Santa Cecilia. Infine, come abbiamo visto, giocando tra primo piano e sfondo, mette in relazione Santa Cecilia con la statua accanto all’ingresso -Santa Caterina d’Alessandria-, entrambe attribuite al Maestro di Sant’Anastasia.

Scarpa non ha bisogno di frecce o cartelli, e invece prepara un’esca, una trappola in cui attirare il visitatore, per fargli fare determinati movimenti e guardare determinate cose.

La scultura che volge la schiena al visitatore, che ne condiziona l’attenzione e i movimenti ripropone la strategia espositiva e didattica che abbiamo già visto a Palazzo Abatellis (link).

Ma qui tutto il contesto è diverso ed è coerente con quella strategia.

Perché questa differenza con Palazzo Abatellis?

Il fatto è che, qui a Castelvecchio, Scarpa ha goduto di molta più libertà. La ricostruzione dopo i bombardamenti della guerra gli ha consentito di coniugare e ibridare restauro e nuova architettura, mettendo a confronto i linguaggi e le tecniche della storia e della contemporaneità. Gli ha permesso di mostrare che antico e moderno possono non essere antitetici: come a Venezia, dove Scarpa era nato e si ea formato, e dove le architetture di tanti secoli si compongono in un’armonia fantastica.

E in questo gioco di ibridazione Scarpa ha inserito anche le opere d’arte.

Rivediamo l’insieme.

In un’analogia con l’architettura classica, potremmo dire che nella Galleria delle Sculture Scarpa prima di tutto predispone un ‘ordine maggiore’: un percorso assiale che attraversa tutta quest’ala del castello.

Il visitatore, subito dopo la biglietteria, fin dalla soglia della prima sala vede il punto d’arrivo in fondo alla galleria, l’uscita in fondo al cannocchiale disegnato dagli archi che tagliano le spesse murature.

All’interno di questo ordine maggiore, in ogni sala Scarpa introduce poi gli ‘ordini minori’, ossia i percorsi secondari che si diramano dall’asse centrale.

In una diversa analogia, potremmo dire che il percorso espositivo adotta una narrazione a ‘cornice’, o forse più precisamente una narrazione ‘a incastro’ (entrelacement, nella terminologia francese): una narrazione sempre sospesa che allaccia e lega tra loro storie diverse, differenti episodi. E’ la tecnica di molti capolavori della letteratura di tutti i tempi e di tutti i luoghi, come Le Mille e una notte, il Decamerone, l’Orlando Furioso, etc. [1]

Ed è proprio così che nella Galleria delle Sculture la visione simultanea, dell’insieme, offerta dal cannocchiale -la cornice- allaccia e lega tra loro i percorsi secondari -i differenti episodi, i differenti gruppi di sculture-. I mezzi che legano il percorso principale ai percorsi secondari -la cornice ai singoli episodi- sono le soglie e i traguardi. [2]

Gli archi sono le soglie delle sale. Sulla soglia di ogni sala si apre lo spettacolo delle ‘storie diverse’ raccontate dalle opere, che dialogano tra loro e che trascinano il visitatore su traiettorie trasversali, come abbiamo visto nella seconda sala.

Gli archi circoscrivono altrettanti traguardi, esattamente come la finestra sul lago di Le Corbusier (link). Ma gli archi non sono i soli elementi che scandiscono il cammino: anche alcune opere che sembrano ‘ingombrare’ il percorso centrale giocano in contrappunto con soglie e traguardi.

Queste opere -l’arca con i Santi Sergio e Bacco, nella prima sala, (7.5, a sinistra, sullo sfondo), la pedana con due statue che abbiamo visto nella seconda sala (7.4) e San Pietro in trono nella quinta e ultima sala (7.10)- già da lontano concorrono a legare tra loro le sale e le altre opere esposte, cioè ad anticipare e a intrecciare tra loro la cornice generale e le storie diverse.

In questo modo la visione d’insieme suggerisce al visitatore anche un esame più attento, analitico, che non si limita al confronto tra le opere, ma guida anche alla scoperta dei dettagli.

Allargando lo sguardo oltre le opere, ad esempio, ci si accorge che tutte le sale sono attraversate da strisce di marmo chiaro ortogonali al percorso principale: ancora soglie, appunto, che scandiscono e misurano la posizione delle opere e che tacitamente invitano a rallentare, ad andare a destra, o a sinistra.

Come abbiamo cominciato a vedere, nella Galleria delle Sculture di Castelvecchio, a differenza di Palazzo Abatellis, Scarpa può intervenire sul luogo ospite, trasformandolo in quello abbiamo definito luogo dell’esposizione, o luogo della mostra.

Ma in questa operazione Scarpa non cerca di ricostruire, di simulare i perduti luoghi d’origine delle sculture. Fa invece vedere che anche le sculture sono a loro volta ‘luoghi’, sono riconoscibili per memoria e per forma. Come ‘luoghi’ Scarpa dispone le sculture a dialogare con il luogo che le raccoglie. Un luogo che Scarpa vuole diverso per memoria e per forme, poiché la diversità di linguaggi tra luogo ospite e opere esposte può dare risalto, può dar voce al racconto delle sculture.

Così, alla fine, le sculture ‘abitano’ lo spazio e lo spazio ordina e trae un senso dalle sculture.

E’ un concetto importante. Per meglio comprenderne le inerenze, guardiamo ancora, in particolare, uno degli episodi che costellano il percorso centrale.

Nella quarta sala, infatti, Scarpa fa un’operazione ardita.

Il visitatore, entrando nella sala, scopre a fianco all’arco (7.7) quella che a prima vista sembra una classica Crocifissione: ha di fronte a sé lo straordinario e impressionante ‘Cristo urlante’ -ancora del Maestro di Sant’Anastasia- e, ai suoi piedi, la Madonna e San Giovanni, disposti secondo l’iconografia tradizionale.

Che cosa succede?

E’ mai possibile che Scarpa simuli un’ipotetica disposizione originale delle tre sculture? Che adotti qui una logica espositiva completamente opposta a quella che configura tutto il resto della galleria?

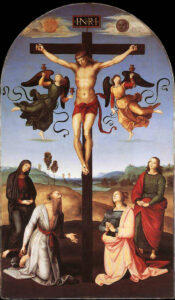

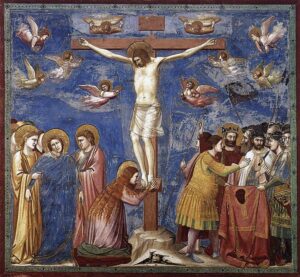

In realtà non è così. Basta confrontare la messa in scena di Scarpa con una qualsiasi Crocifissione -si pensi per esempio ad opere di Raffaello (7.8) o di Giotto (7.9)- per comprendere che Scarpa evoca la tradizione soltanto per esibirne le siderali differenze.

Nell’allestimento di Scarpa le tre figure appaiono isolate, dissonanti tra loro, ognuna congelata nella sua disperata solitudine, nessuno guarda o sembra rivolgersi a nessun altro.

L’ordine perfetto, la sovrumana compostezza del quadro di Raffaello -e dei milioni di santini che ha ispirato-, il perfetto equilibrio della composizione canonica, qui tutto è fracassato dall’urlo senza voce del Cristo.

Ogni divina distanza dalle cose del mondo, ogni angelica armonia, ogni possibile regalità delle tre figure, tutto sembra oscurato.

Il cielo scompare, resta la carne dolente. Per chi è lì, a guardare, non resta che la compassione, l’umana vicinanza, la terrena pietà.

Dunque, in questo racconto, in questo inciso lungo il percorso principale, Scarpa non ricorre alla simulazione. Invece mette in scena una rappresentazione, anzi, una sacra rappresentazione, per coinvolgere l’osservatore e mettere a confronto l’oggetto d’arte e il suo messaggio spirituale. Evoca la memoria di quei santini che ogni buon cristiano porta con sé per mostrare la travolgente differenza, l’anomalia tutta umana di quell’opera d’arte.

Una domanda: perché rappresentare e non simulare?

La simulazione, l’imitazione di qualcosa, conferma l’osservatore in ciò che già conosce, lo rassicura, in sostanza lo mantiene passivo. La rappresentazione, al contrario, lo coinvolge, esige l’esercizio del suo giudizio critico: in sostanza lo rende attivo.

Scarpa, nella Crocifissione non simula l’iconografia tradizionale, e nel resto della galleria non simula un’architettura coeva alle sculture.

Strania definitivamente le opere dai loro contesti d’origine.

Costruisce per loro un nuovo luogo differente per memoria e per forme, poiché la diversità di linguaggi tra luogo d’origine e luogo creato dall’allestimento, e tra questo e le opere esposte, consente di dare risalto, di dar voce al racconto delle sculture.

In questo modo l’allestimento risveglia la nostra attenzione dal sonno delle quiete abitudini, e ogni opera d’arte non è più solo il reperto -ciò che resta- di un mondo perduto, ma rivive nel nuovo ordine creato per lei.[3]

Alla fine, ogni sala -ognuna con le sue storie- e l’insieme delle sale costituiscono un unico spazio rigoroso e coerente, un’unica composizione di masse, di superfici, di gruppi di sculture, di pedane che volano, di basi che gravano, di traguardi e di cadenze tracciate sul pavimento come su un pentagramma. Una composizione di materie povere e materie preziose, di linguaggi e di forme antiche e nuove, sulle quali le luci naturale e artificiale giocano con il lucido e l’opaco delle superfici, e poi con i grigliati, con gli incastri, con ogni apparente particolare.

Un’unica logica espositiva per un racconto unitario.

Qui, nella Galleria delle Sculture di Castelvecchio, Scarpa realizza un autentico capolavoro, un luogo complesso, nel quale è davvero difficile distinguere architettura e allestimento espositivo.

A Castelvecchio appare ancora una volta e con rara chiarezza che l’allestimento è un metalinguaggio in grado di mettere insieme e rendere reciprocamente incidenti tutti i linguaggi in gioco.

…

Per meglio comprendere l’unitarietà, l’inseparabilità di opere, allestimento e architettura, possiamo lavorare di immaginazione.

Cosa accadrebbe se portassimo via le sculture e i loro basamenti dalle sale della Galleria? Resterebbe una sequenza di eleganti sale, magari pronte per qualsiasi uso. Ma le strisce trasversali di marmo chiaro diventerebbero inutili, insignificanti: puri elementi decorativi, del tutto insufficienti a scandire o competere con la fuga prospettica dell’infilata delle sale.

Cosa accadrebbe se, invece, cancellassimo le strisce trasversali?

Allora sculture e basamenti, senza il pentagramma che li connette, resterebbero da soli, come corpi sospesi nel vuoto, a comporre l’ordine delle loro relazioni reciproche e ad articolare lo spazio di ogni sala. L’architettura intorno -fatto salvo il ritmo degli archi e il gioco delle luci- potrebbe essere allora intercambiabile con un qualunque magazzino, un contenitore privo di ogni ‘contatto’ con le opere.

E, infine, non possiamo neanche immaginare di eliminare i basamenti -i tappeti volanti, o i blocchi di cemento e/o acciaio-: posare le statue sul pavimento significherebbe perdere la misura dei rapporti tra ognuna di esse e visitatore, e sarebbe come cancellare i capitelli tra colonne e architravi di un tempio dorico.

Torniamo alle riflessioni su percorso, soglie e traguardi.

Segnaliamo, soltanto per inciso, che il visitatore ne troverà altri, -forse più ‘semplici’, meno densi di relazioni-, anche nella pinacoteca e nelle sale ai piani superiori.

In una sala (7.6), ad esempio, guardando la lunga tavola (forse una predella) sulla parete, si intravede di fianco, a sinistra, sotto vetro, quella che sembra un’icona da viaggio, mentre poco più in là il vano di una porta inquadra perfettamente un trittico.

Come nel caso della testa di Eleonora a Palazzo Abatellis (link), è un gioco di anticipi, per mostrare al visitatore dove lo condurrà il percorso? Oppure Scarpa ha voluto porre in relazione tra loro i tre pezzi?…

Anche qui, come sempre, il gioco dei traguardi non si chiude tra le opere esposte, ma è voluto per coinvolgere il visitatore, per incuriosirlo, seminando silenziose domande.

In breve, Castelvecchio ci fa capire ancora una volta come, ad ogni passo, i riscontri tra quanto appare di fronte e quanto resta sullo sfondo, i giochi di soglie e traguardi, perfino quelli che possono apparire degli ostacoli, degli inciampi, perfino degli errori, lungo la linea teorica di un percorso, possano essere invece artifici della narrazione, strumenti fondamentali per cadenzare e guidare i passi del visitatore, per attirarlo, per orientarne l’attenzione sulle proprietà degli oggetti esposti, per condizionarne e configurarne l’esperienza.

…

Riflettendo più in generale, è ovvio che, una volta entrati nel gioco di Scarpa, diventa forte il rischio di fraintesi. Si potrebbe cioè arrivare a porsi domande anche fuori luogo o a prendere per ragioni compositive quelle che sono soltanto fantasie di uno sguardo troppo malizioso. D’altra parte, è appunto un gioco voluto da Scarpa, e alle sue tentazioni è difficile sottrarsi.

Ad esempio, sbirciando dalla quarta alla quinta sala, oltre l’arco a destra della Crocifissione, Scarpa ci fa intravedere la figura di San Pietro in trono, di Bartolomeo Giolfino, del XV secolo, quella che invade il percorso principale (7.10). E’ solo l’ultima scultura, resa visibile fin dall’ingresso nella Galleria, per segnalare la fine del percorso? Oppure è un’allusione? Allude a Pietro, ben lontano da Gesù al momento del martirio, o allude alla Chiesa che poi verrà e al suo primo papa? Chissà?

E ancora, tornando nella prima sala, potrebbe venire il delizioso dubbio che l’ironia e un pizzico di vanità abbiano guidato la mano di Scarpa quando ha disegnato i basamenti in cemento e acciaio su cui posa -quasi sospesa- l’arca con i Santi Sergio e Bacco. Questi basamenti non sembrano fare il verso -quasi da ‘colleghi’- ai i gobbi che poco più in là, sullo sfondo, si piegano sotto una pesante lastra in pietra, quel che resta forse di un pulpito o di un ambone ? (7.11)

Infine, il primo e ultimo traguardo (7.12). Quando si entra al Castello, o se ne esce, sulla soglia e sul ponticello che scavalca il fossato -e che porta al giardino e alla biglietteria -, a sinistra si vede da lontano la statua equestre di Cangrande della Scala, inserita in un complesso incastro di nuova architettura e di restauro del castello.

Bisognerà attraversare tutta la Galleria delle Sculture per arrivare ai suoi piedi e poter finalmente guardarla da vicino…

Cangrande, dunque, è là soltanto per diventare l’icona del Museo di Castelvecchio, o è anche la dichiarazione di una metodologia espositiva?

…

Un’ultima considerazione.

Il perché di una mostra d’arte -ça va sans dire- si concretizza primariamente nella selezione delle opere, nelle ragioni esplicite delle presenze e nelle ragioni implicite delle assenze.

Ma la rappresentazione, l’esposizione del perché di una mostra -ripeto ancora una volta- non può essere affidata soltanto ai titoli, alle parole, a uno qualunque dei molti modi in cui la parola scritta o parlata può essere presente.

Le ragioni devono essere mostrate proprio come le opere, devono essere rese riconoscibili, visibili per mezzo delle opere: dunque con gli stessi linguaggi, con le stesse forme della mostra, attraverso la composizione di sfondi e contesti, attraverso i confronti mirati tra determinate opere e l’ordinamento di questi confronti, attraverso i giochi che abbiamo visto.

La necessità di affidarsi ai titoli, alle parole, ai cartelli per un allestitore equivale in qualche modo ad una dichiarazione di impotenza. O, rovesciando i termini, l’efficacia, il fascino di una mostra -e del suo allestimento- è inversamente proporzionale alla quantità dei testi esplicativi.

Lo stesso concetto può essere espresso in termini diversi.

In altre clip ho suggerito l’idea di pensare la mostra come una metafora di un discorso, di un racconto: una metafora concreta, fatta di cose e di azioni. Parlavo della retorica antica, secondo la quale lo scopo del discorso è convincere l’ascoltatore, e parlavo delle analogie tra le fasi di preparazione -di progetto- del discorso e del percorso espositivo.

Parafrasando i termini e le operazioni della retorica antica, potremmo dire che, a Castelvecchio, nella Galleria delle Sculture Scarpa ci regala un fantastico saggio di efficacia e di coerenza tra inventio -la scelta degli argomenti, cosa mettere in evidenza-, dispositio -l’ordinamento, la logica, delle opere lungo il percorso-, elocutio -il modo più attraente, più coinvolgente di esporre ogni singola opera e/o ogni gruppo di opere- e l’actio -i gesti, i movimenti, perfino le emozioni progettate per il visitatore-.

Anche in questo insegnamento appare il genio di Scarpa.

[1] Per una interessante analisi della struttura narrativa della Galleria delle Sculture, vedi anche il saggio di Filippo Bricolo, Carlo Scarpa ed il racconto di Castelvecchio. Analisi narratologica della Galleria delle Sculture, https://www.famagazine.it/index.php/famagazine/article/view/166/876

[2] A proposito di soglie e traguardi, cfr. clip 5

[3] i termini rappresentazione, simulazione, straniamento rimandano ad altrettanti metodologie e a essenziali repertori strumentali dell’allestimento. La loro trattazione ci porterebbe lontano dai temi di questa lezione. Torneremo dunque a parlarne in una delle prossime clip.

…………………………………………………………………………………………….

![]()

exhibition staging and architecture

Carlo Scarpa was perhaps the greatest and unsurpassed master in the ‘mise en scéne’ of the works of art: finding the place, the orientation, the light, the most appropriate visibility conditions for each single piece. But he was also master in directing the paths for the visitor, in the composition of contexts, backgrounds, feedback.

It is not possible, here, give an exhaustive report of his extraordinary work as staging designer.

We have already seen some rooms of Palazzo Abatellis in Palermo (1953-1954), but also in another of his masterpieces, the Museum of Castelvecchio in Verona (1958-1975), we can find evidence of his magic as a great seducer.

…

On the ground floor of Castelvecchio, after the ticket office, the visitor turns left and -climbed a step that marks the threshold- overlooks the five rooms of the Galleria delle Sculture -the Sculpture Gallery- (7.1).

Five rooms, in which are mainly lime and concrete in different variations to offer the material that is the background to the sculptures: clear walls of rough lime perimeter floors in hammered concrete plates. On the plates are firmly laid polished concrete or steel bases, or -on the contrary- seem to levitate -like flying carpets- black lime platforms shiny like mirrors. (7.3)

Stopping for a moment on the threshold of the second room, the visitor -if he has never been to Palazzo Abatellis- finds an oddity: a statue turns its back. Then, turning his gaze, he discovers that none of the sculptures is facing him -towards the entrance-, because even the only figure placed frontally -on the back wall- looks elsewhere (7.2).

So, after observing the drapery that falls from the shoulders of the statue, curious, instinctively the visitor advances, and he tries to see their faces, as with real people who are presented to him.

Walking, he probably stops and looks to the right, to observe the pair of statues whose platform -attention! – clutter the central path (7.4).

From this new position, the statue that showed his shoulders now is visible by three-quarters. So the visitor moves forward again, and goes around it.

Finally, he sees the statue in front (7.5). From the musical instruments he can understand that it is Santa Cecilia. He still observes it well, and then, inevitably, he compares it with that one on the back wall, next to the entrance, also now facing frontally.

It is now clear that the apparent weirdness has very good reasons.

Without arrows or signs, Scarpa induces -almost forcing him?- the visitor to leave the central path, first avoiding the platform with the pair of statues, then turning around Santa Cecilia. Then, as we have seen, between the foreground and background, he relates this one to the statue next to the entrance -Saint Catherine of Alexandria-, both attributed to the Master of Saint Anastasia.

Scarpa does not need arrows or signs, simply because he prepares a bait, a trap in which to attract the visitor, to make him make certain movements and look at certain things.

The sculpture that show the back to the visitor, that conditions his attention and movements proposes again the expositive and didactic strategy that we have already seen to Palazzo Abatellis (link).

But here the whole context is different and is consistent with that strategy.

Why this difference with Palazzo Abatellis?

The fact is that, here in Castelvecchio, Scarpa has enjoyed much more freedom. The reconstruction after the bombing of the war allowed him to combine and hybridize conservation and new architecture, comparing the languages and techniques of history and modernity. It allowed him to show that ancient and modern can not be antithetical: as in Venice, where Scarpa was born and trained, and where the architecture of different centuries are composed in a fantastic harmony.

And in this hybridization game Scarpa has also included the works of art.

Let’s review the whole.

In an analogy with classical architecture, we could say that in the Galleria delle Sculture Scarpa, first of all, prepares a ‘major order’: an axial path along the entire wing of the castle.

The visitor, right after the ticket office, from the threshold of the first room sees the point of arrival, the exit at the bottom of the telescope designed by the arches that cut the thick walls.

Within this ‘major order’, in each room Scarpa then introduces the ‘minor orders’, the secondary paths that branch off from the central axis.[1]

In a different analogy, we could say that the exhibition path adopts a ‘frame’ narrative, or perhaps more precisely ‘interlocking’ narrative (entrelacement, in French terminology): an ever-suspended narrative that links and binds different stories, different episodes. It’s the technique of many masterpieces of literature of all time and all places, like The Arabian Nights (The Thousand and One Nights), the Decameron, the Orlando Furioso, etc.

And it is precisely in this way that in the Galleria delle Sculture the simultaneous vision of the whole offered by the telescope -the frame- links and ties together the secondary paths -the different episodes, the different groups of sculptures-. The means that link the main path to the secondary paths -the frame to the different stories- are the thresholds, lines of sight and framing plays.[2]

The arches are the thresholds of the rooms. On the threshold of each room opens the spectacle of the ‘different stories’ told by the works, which dialogue with each other and drag the visitor along transversal trajectories, as we saw in the second room.

The arches circumscribe as many frames, just like the window on the lake by Le Corbusier (link). But the arches are not the only elements that mark the path: even some works that seem to ‘clutter’ the central path play in counterpoint with thresholds and lines of sight. These works -the arca con i Santi Sergio e Bacco, in the first room, (7.5, left, in the background), the platform with two statues that we saw in the second room (7.4) and San Pietro in trono in the fifth and last room (7.10)- already from a distance they take part to link the rooms and the other works on display, that is, to anticipate and intertwine the general frame and the different stories.

In this way the overall view also suggests to the visitor a more careful, analytical examination, which is not limited to the comparison between the works, but also guides to the discovery of details.

For example, broadening the gaze beyond the works, the visitor realizes that all the rooms are crossed by strips of light marble orthogonal to the main path: again thresholds, in fact, which mark and measure the position of the works and which tacitly invite you to slow down, to go to right, or left.

As we began to see, in Castelvecchio, unlike Palazzo Abatellis, Scarpa can intervene on the host site, transforming it into the exhibition site.

But in this operation Scarpa does not try to reconstruct, to simulate the lost sites of origin of the sculptures. Instead, he shows that even the sculptures are ‘places’, they are recognizable by memory and shape. As ‘sites’ Scarpa arranges the sculptures to dialogue with the site that collects them. A site that Scarpa wants to be different in terms of memory and forms, because the diversity of languages between the host site and the works on display can give prominence, can give voice to the story of the sculptures.

Thus, finally, the sculptures ‘inhabit’ space and space orders and draws a sense from the sculptures.

It’s a fundamental concept. To better understand its inherencies, let us look again, in particular, at one of the episodes that dot the central path.

In the fourth room, in fact, Scarpa does a daring operation.

Upon entering the room, the visitor discovers next to the arch (7.7) what at first sight appears to be a classic Crucifixion: in front of him is the extraordinary and impressive ‘Crying Christ’ -again by the Master of Sant’Anastasia- and, at its feet, the Madonna and San Giovanni, arranged according to traditional iconography.

What happens?

Is it ever possible that Scarpa simulates a hypothetical original arrangement of the three sculptures? Who here adopts an exhibition logic that is completely opposite to that which shapes the rest of the gallery?

Actually, it’s not like that. It is enough to compare the Scarpa’s staging with any Crucifixion -think for example of works by Raphael (7.8) or Giotto (7.9)- to understand that Scarpa evokes tradition only to show the sidereal differences.

In Scarpa’s staging the three figures appear isolated, dissonant from each other, each frozen in its desperate solitude, no one looks or seems to notice anyone else.

The perfect order, the superhuman composure of Raphael’s painting -and the millions of holy cards he inspired-, the perfect balance of the canonical composition, here everything is shattered by the voiceless cry of Christ.

Every divine distance from the things of the world, every angelic harmony, every possible royalty of the three figures, everything seems obscured.

The sky disappears, only painful flesh remains. For those who are there, to watch it, alla that remains is compassion, human closeness, earthly mercy.

Therefore, in this story, in this branch along the main path, Scarpa does not resort to simulation. Instead he stages a representation, or -better- a sacred representation, in which to compare the objet of art and its spiritual message. He evokes the memory of those holy cards that every good Christian carries with him to show the rousing difference, the entirely human anomaly of that work of art.

A question: why represent and not simulate?

The simulation, the imitation of something, confirms the observer in what he already knows, reassures him, basically keeps him passive. The representation, on the contrary, involves him, demands the exercise of his critical judgment: basically it makes him active.

Scarpa, in the Crucifixion does not simulate the traditional iconography, and in the rest of the gallery he does not simulate architecture coeval with sculptures.

Definitely he alienates the works from their original contexts.

He builds for them a new site different for memory and for forms, because the diversity of languages between site of origin and site created by the exhibition, and between this and the exhibited works, allows to give prominence, to give voice to the story of the sculptures.

In this way the exhibition awakens our attention from the sleep of quiet habits, and every work of art is no longer just the artifact -what remains- of a lost world, but relives in the new order created for it.[3]

Finally, each room -each with its own stories- and the whole of the rooms constitute a single rigorous and coherent space, a single composition of masses, of surfaces, of groups of sculptures, of platforms that fly, bases that weigh down, lines of sight and cadences traced on the floor as on a pentagram. A composition of poor materials and precious materials, of ancient and new languages and shapes, on which natural and artificial lights play with the glossy and opaque of the surfaces, and with the gratings, with the joints, with every apparent detail. A single logic of exhibition staging for a unitary story.

Here, in the Galleria delle Sculture in Castelvecchio, Scarpa creates an authentic masterpiece, a complex place, in which it is really difficult to distinguish architecture and exhibition staging.

In Castelvecchio it appears once again with rare clarity that the staging is a metalanguage able to put together and to affect reciprocally all the languages involved.

…

To better understand the unity, the inseparability of works, exhibition staging and architecture, we can work whit imagination.

What would happen if we took away the sculptures and their bases from the rooms of the gallery?

It would remain a sequence of elegant rooms, perhaps ready for any use. But the transverse stripes of light marble would become useless, insignificant: pure decorative elements, completely insufficient to mark or compete with the perspective escape of the room.

What would happen if, instead, we erased the transverse stripes?

In this case sculptures and bases, without the pentagram that connects them, would remain alone, like bodies suspended in the void, to compose the order of their reciprocal relations and to articulate the space of each room.

The architecture around -except for the rhythm of the arches and the play of lights- could then be interchangeable with any warehouse, a container without any ‘contact’ with the works.

And, finally, we cannot even imagine eliminating the bases -the flying carpets, or the concrete and/or steel blocks-: placing the statues on the floor would mean losing the measure of the relationship between each of them and visitor, and would be like eliminating the capitals between columns and architraves of a Doric temple.

Let’s go back to the reflections on the path, thresholds and frames -or lines of sight-.

We point out, only incidentally, that the visitor will find other of them -perhaps more ‘simple’, less dense of relationships-, even in the picture gallery and in the rooms on the upper floors.

In a room (7.6), for example, looking at the long table (perhaps a predella) on the wall, you can see on the side, on the left, under glass, what looks like a travel icon, while, a little further on, the compartment of a door perfectly frames a triptych.

As in the case of the head of Eleonora at Palazzo Abatellis, is that a game of advances, to show the visitor where the path will lead him? Or did Scarpa want to relate the three pieces to each other?…

Here too, as always, the game of lines of sight does not close among the works on display, but is intended to involve the visitor, to intrigue him, sowing silent questions.

Here too, as always, the game of traguardi does not end between the works on display, but is intended to involve the visitor, to intrigue him, sowing silent questions.

In short, Castelvecchio makes us understand once again how, at every step, the feedback between what appears in front and what remains in the background, the games of thresholds and lines of sight even those that may appear obstacles, stumbling blocks, even errors, along the theoretical line of a path, they may be instead artifices of the narrative, fundamental tools for cadencing and guiding the steps of the visitor, for attracting him, for directing his attention on the properties of the exposed objects, for conditioning and configuring his experience.

…

Reflecting more generally, it is obvious that, once you get into Scarpa’s game, the risk of misunderstandingsbecomes strong. You could get to ask yourself misplaced questions, or to take for compositional reasons those that are only fantasies of a look too mischievous. On the other hand, it is a game wanted by Scarpa, and his temptations are difficult to escape.

For example, looking from the fourth to the fifth room, through the arch on the right of the Crucifixion, Scarpa lets us glimpse the figure of San Pietro in trono, by Bartolomeo Giolfino, of the fifteenth century, which invades the main path (7.10).

Is it just the last sculpture, made visible from the moment you enter the gallery, to signal the end of the path? Or is it an allusion? Does he allude to Peter, far removed from Jesus at the moment of martyrdom, or does he allude to the Church that will then come and to its first pope? Maybe?

And again, returning to the first room, the delightful doubt could arise that irony and a pinch of vanity guided Scarpa’s hand when he designed the concrete and steel bases on which he laid -almost suspended- the arca con i Santi Sergio e Bacco. Don’t these bases seem to mimic -almost like ‘colleagues’- to the hunchbacks that a little further on, in the background, bend under a heavy stone slab, perhaps what remains of a pulpit or an ambo? (7.11)

Finally, the first and final framing play (7.12). When you enter the Castle, or live it, on the threshold and on the bridge that crosses the moat -and that leads to the garden and the ticket office-, on the left you can see from a distance the equestrian statue of Cangrande della Scala, placed in a complex interlocking of new architecture and restoration of the castle.

You’ll have to go through the entire Galleria delle Sculture to get to her feet and finally be able to look at her up close…

Cangrande, then, is there only to become the icon of the Museum of Castelvecchio, or is it also the declaration of an exhibition methodology?

…

One last point.

The reason for an art exhibition -ça va sans dire- is primarily expressed in the selection of works, in the explicit reasons of presences and in the implicit reasons of absences.

But the representation, the exposition of the reason of an exhibition -I repeat once again- cannot be entrusted only to the titles, to the words, to any of the many ways in which the written or spoken word can be present.

The reasons must be shown just like the works, must be made recognizable, visible through the works: therefore with the same languages, with the same forms of the exhibition, through the composition of backgrounds and contexts, through targeted comparisons between certain works and the ordering of these comparisons, through games we have seen.

The need to rely on titles, words, signs for an staging designer is in some way a declaration of impotence. Or, reversing the terms, the effectiveness, the fascination of an exhibition -and its staging- is inversely proportional to the quantity of explanatory texts.

The same concept can be expressed in different terms.

In other clips I suggested the idea of thinking of the exhibition as a metaphor of a speech, of a story: a concrete metaphor, made of things and actions. I was talking about the ancient rhetoric, according to which the purpose of the speech is to convince the listener, and I was talking about the similarities between the phases of preparation -project- of the speech and the exhibition path.

Paraphrasing the terms and operations of ancient rhetoric, we could say that, in Castelvecchio, in the Galleria delle Sculture Scarpa gives us a fantastic essay of effectiveness and coherence between inventio -the choice of arguments, what to highlight-, dispositio -the ordering, the logic, of works along the way-, elocutio -the most attractive, most engaging way to staging each individual work and/or each group of works- and the actio -the gestures, the movements, even the emotions designed for the visitor-.

The genius of Scarpa also appears in this teaching.

[1] For an interesting analysis of the narrative structure of the sculpture gallery, see also the essay by Filippo Bricolo, Carlo Scarpa e il racconto di Castelvecchio. Analisi narratological della Galleria delle Sculture.

[2] About thresholds and traguardi -frame or line of sight- see clip 5.

[3] the terms representation, simulation, estrangement refer to as many methodologies and essential instrumental repertoires of the exhibition staging. Their treatment would take us away from the themes of this lesson. So we will talk about it again in one of the next clips.

7.0 Castelvecchio, Verona

https://siviaggia.it/idee-di-viaggio/5-castelli-raccontano-storia-provincia-scaligera/313458/

7.1 C.Scarpa, Museo di Castelvecchio, Verona (1958-1975) – Galleria delle Sculture, pianta

7.2 entrando nella seconda sala

7.3 particolare della pavimentazione in cemento e marmo bianco

7.4

7.5 Maestro di Sant’Anastasia (attr.) Santa Cecilia, e in secondo piano Santa Caterina di Alessandria (sec. XIV)

7.6 una sala della pinacoteca

7.7 Galleria delle Sculture, quarta sala – Maestro di Sant’Anastasia, Crocifissione, Madonna e San Giovanni (sec. XIV)

7.8

Raffaello Sanzio, Crocifissione Mond o Gavari, olio su tavola, 1502-1503

National Gallery, Londra

https://it.wikipedia.org/wiki/Crocifissione_Gavari

7.9

Giotto, Crocifissione, affresco, 1303-1305

Cappella degli Scrovegni, Padova

https://it.wikipedia.org/wiki/Crocifissione_(Giotto)

7.10 quinta e ultima sala – Bartolomeo Giolfino, San Pietro in trono (sec. XV)

7.11 prima sala, Arca dei Santi Sergio e Bacco, dettaglio del basamento

7.12 Castelvecchio – l’ingresso al giardino e statua equestre di Cangrande della Scala