site & exhibition

Castello di Rivoli, Villa Borghese a Roma

Alberto Giacometti a Roma e a Venezia

Abbiamo visto palazzo Abatellis (clip 05) e Castelvecchio (clip 07), dove Carlo Scarpa con magistrali interventi di restauro di edifici semidistrutti dalla guerra ha realizzato opere che mettono insieme -ogni volta in un unicum irripetibile- storia, architettura e allestimento.[1]

E abbiamo visto, nelle corti di Castelgrande e del Maschio Angioino (clip 08), in luoghi presi in prestito ed intoccabili, in quale modo determinate loro caratteristiche abbiano potuto essere usate come componenti nell’allestimento.

Esaminiamo ora altri tre casi.

1.

Il Castello di Rivoli (9.1), non lontano da Torino, nel corso dei secoli è stato troppe volte costruito, distrutto e ricostruito. Residenza dei Savoia, caserma, perfino casinò. Oggetto nel tempo di cento progetti -anche di Filippo Juvarra nel 1700-, ha visto cento volte l’inizio di fastosi lavori di ricostruzione e di completamento, e altrettante volte la loro interruzione. Distrutto ancora e in gran parte durante l’ultima guerra, poi di nuovo abbandonato e fatiscente, soltanto alla fine degli anni ’70 del ‘900 la Regione Piemonte decide di restaurarlo e di farne la sede dell’attuale Museo d’Arte Contemporanea.

L’intervento fu affidato all’architetto Andrea Bruno. Nel sito del Castello si legge che la scelta -a mio avviso geniale- fu quella di mantenere le testimonianze superstiti dando importanza a tutti i momenti della vita del Castello, partendo dall’interruzione del cantiere juvarriano, passando per il lavoro di fine settecento di Carlo Randoni sino agli interventi per i militari. Andrea Bruno evita di realizzare falsificazioni e completamenti, rispettando l’architettura, che diventa immagine reale della storia e delle vicissitudini della struttura. Ed ecco che esternamente come internamente sono stati conservati stucchi, cornici, dipinti danneggiati dalle ingiurie del tempo e dall’incuria degli uomini.

Dopodiché, dall’inaugurazione ad oggi, in quarant’anni, anche l’allestimento di decine di mostre non ha mai fatto sentire il bisogno di modificare niente di sostanziale del luogo ospite. Dalle iniziali collezioni di arte povera, le stesse sale del castello hanno ospitato magnificamente autori ed opere d’arte contemporanea, anche completamente differenti.

Com’è possibile? Basta un rapido reportage, basta mettere a confronto gli stessi luoghi e artisti diversi per iniziare a comprendere quello che succede (vedi ad esempio 9.2/9.3/9.4 e anche 9.5/9.6).

Va da sé che girare fisicamente per le sale del Castello di Rivoli è un’esperienza che queste note non possono né evocare, né tantomeno sostituire. Ma le immagini forse sono sufficienti per capire che tutto si gioca sui traguardi, ossia -in questo caso- tra le opere e il contesto in cui sono inserite, tra le opere e ciò che resta del Castello (9.7/9.8).

A Rivoli l’arte contemporanea può trionfare, può esprimere tutta la sua potenza rivoluzionaria e vitale proprio perché si staglia sulle macerie di antichi splendori aristocratici e borghesi.

Il cupo fascino del Castello di Rivoli, di un aggregato di spazi mai finiti, abbandonati, fatiscenti, congelati in frammenti malinconici, è la metafora della fine della bellezza istituzionale, di un’idea di bellezza che celebra il potere.

Diventa -o rappresenta- la morte di quell’arte.

Diventa il terreno fecondo -sfondo e materia- della nuova arte…

2.

Il secondo caso è paradossalmente agli antipodi.

Guardando il Castello di Rivoli e la Villa Borghese a Roma, potremmo parlare della forza di seduzione, ma anche del problema, che si cela nello squilibrio, nello scarto tra luogo ospite e mostre ospitate, tra la materia e i linguaggi del primo e quelli delle opere esposte.

Nella mostra Giacometti. La scultura alla Galleria Borghese di Roma, nell’omonima villa, nel 2014, in un audace esperimento, veniva messa a confronto la tragica modernità di Giacometti, anti-monumentale eppure straordinaria, con la grande -e monumentale- scultura classica.

Un esperimento coraggioso -per la cura di Anna Coliva e Christian Klemm, con l’allestimento di Daniela Ferretti- portato avanti proponendo -appunto- allineamenti, traguardi, riscontri tra coppie o gruppi di opere, mostrando analogie e -soprattutto- differenze anche illuminanti, come tra l’Uomo che vacilla e il David di Bernini (9.9), o tra la ieratica Donna che cammina e l’intera sala egizia (9.10), mostrando anche lo straniamento, la solitudine straziante, dell’ Homme qui marche nel salone d’ingresso della Galleria (9.12)…

Era un esperimento che può aprire nuove strade allo studio e alla critica d’arte. Tanto più coraggioso poiché non è facile mettere a confronto in uno unico spazio opere appartenenti a secoli o millenni differenti, come si era visto con la mostra su Henry Moore alle Terme di Diocleziano, o in altre mostre organizzate in vari musei d’Italia.

Come al solito, ai fini delle riflessioni che stiamo portando avanti la nostra attenzione non va alla mostra in generale, ma si concentra su alcune parti e alcuni aspetti del suo allestimento.

Da un certo punto di vista, infatti, Giacometti alla Galleria Borghese segnala un problema.

Il problema è che a Villa Borghese non ci sono macerie. Il problema è che la Villa, con la stupefacente collezione e la sua compiuta perfezione, era ed è nei secoli dei secoli la spudorata celebrazione del Potere: non soltanto quello dei Borghese, dei Papi, della Roma imperiale, ma il Potere in assoluto. Non casualmente quasi tutti i palazzi del Potere, in tutto il mondo, vestono -o cercano di ostentare- panni analoghi. Siamo, appunto, di fronte ad uno scenario totalmente agli antipodi del Castello di Rivoli.

In questo scenario, il problema è che non solo agli occhi di un visitatore qualsiasi, come me, ma anche per l’obiettivo della macchina fotografica, il confronto non era tra Giacometti e Bernini, o Canova, ma tra Giacometti e tutta la sontuosa, fantastica, ridondanza della Galleria.

All’ingresso, la forte luce diretta, il vuoto e la distanza dalle pareti facevano emergere le sculture dalla relativa penombra del resto del salone (9.12). Ma altrove non vi era modo di trovare un traguardo che desse respiro a Giacometti. Forse -chissà?- per l’impossibilità di spostare i pezzi della collezione permanente, sembrava che a Giacometti fossero rimasti soltanto gli spazi di risulta. E agli occhi del visitatore la dolente -e pur possente- esilità dell’uomo moderno di Giacometti quasi spariva contro lo sfondo delle decorazioni o nei vani delle porte (9.11). Si perdeva nel frastuono visivo della Villa.

Il problema, è, come dicevo, nello scarto tra luogo ospite e mostre ospitate: tra la storia, la consistenza, la materia e i linguaggi del luogo e quelli delle opere esposte.

Proviamo a immaginare un altro scenario.

Chase Manhattan Bank, a New York (9.13), contro Villa Borghese (9.14).

La piazza, i grattacieli, gli stessi ‘abitanti’ di Chase Manhattan Bank, a New York -cui L’homme qui marche, Femme e Tête erano destinati-, sono totalmente anonimi, totalmente banali e intercambiabili con mille altri quasi perfettamente identici in tutti i centri direzionali del mondo.

E come si fa a pensare Villa Borghese come uno spazio anonimo o banale?

E ora immaginiamo di rovesciare il gioco ancora una volta.

Se il confronto tra Giacometti e Bernini fosse stato allestito in una qualsiasi galleria d’arte delle nostre città, con nude pareti bianche o grigie, siamo sicuri che di fronte a L’homme qui marche di Giacometti il David, o l’Apollo e Dafne di Bernini, non sarebbero apparsi come monumentali -e un po’ ridicole- opere in marzapane di un pasticciere pop?

Due annotazioni.

La prima. Alla fine, viene il dubbio che alla Galleria Borghese il cuore vero della mostra fosse non già Giacometti, ma il confronto tra alcuni capolavori della scultura classica e quelli di un grande scultore contemporaneo. Una mostra, dunque, realmente affascinante dal punto vista storico-critico, non con uno, ma con due protagonisti, o meglio: due antagonisti. Il solo problema -dal nostro punto di vista- è che la scultura classica giocava in casa: e non c’è stata partita.

La seconda. Alla fine di queste nostre considerazioni, emerge con tutta evidenza il problema, l’importanza e il fascino della progettazione del luogo della mostra, sia esso il frutto della sapienza nell’uso e riuso di luoghi esistenti oppure un’audace invenzione effimera.

Il tema dell’invenzione del luogo della mostra -che sarà al centro della nostra attenzione nelle prossime clip- può essere introdotto proprio con Scarpa e Giacometti.

Abbiamo detto che non è facile far coesistere e confrontare antico e moderno in un unico spazio o in unica visione dello spazio. Ma non possiamo non pensare alla straordinaria eredità che ci ha lasciato Scarpa, alla sua capacità di avvicinarci all’arte di ogni epoca con i mezzi, con gli occhi e con la sensibilità della modernità, a Castelvecchio, a Palazzo Abatellis, ma anche in tante mostre temporanee.

3.

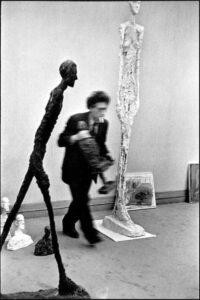

Nel 1962, alla Biennale di Venezia, Scarpa allestisce la sala di Giacometti, che possiamo vedere in una bellissima foto di Ugo Mulas (9.15)

Ad uno sguardo distratto, può sembrare il neutro spazio bianco di una galleria d’arte.

Uno sguardo attento si accorge che le pareti sono bianche, è vero, ma sono quinte: sono aeree superfici staccate dal fondo e tra di loro. Due di esse sono appena incardinate dall’esile cornice dei disegni che gira l’angolo.

Anche Scarpa lavora per sottrazione. Inventa per Giacometti uno straordinario spazio libero, vuoto, definito dall’ordine reciproco di superfici immateriali. La materia è lasciata alle sculture di Giacometti, ai corpi fatti di materia lacerata, corpi immobili o che marciano con tutta la loro energia, assorti sull’orlo di un pensiero -come lo stesso Giacometti in una istantanea di Cartier Bresson a Parigi, l’anno prima, (9.16), o in quella ancora di Mulas durante le fasi di allestimento a Venezia (9.17)-.

Scarpa ha silenziosamente lasciato che le sculture abitassero quello spazio come fossero persone, con la loro coreografia, con i tanti traguardi, allineamenti, e incroci che suggerivano. Ha lasciato che abitassero quello spazio come i visitatori che passavano in mezzo a loro.

Ancora due annotazioni.

A Venezia, come poi si è visto nel salone di Villa Borghese, le sculture di Giacometti mostrano di aver bisogno di spazio, di respiro, ma anche -soprattutto- di stare insieme, come solitudini che hanno bisogno di rispecchiarsi l’una nell’altra (in effetti, come era previsto a New York).

All’interno del Padiglione Italia della Biennale, Scarpa inventa ex novo uno spazio, un luogo per far incontrare Giacometti e i visitatori. Ma proprio là, nel cuore vivo della contemporaneità, Scarpa fa paradossalmente pensare alla Battaglia di San Romano di Paolo Uccello (9.18), ai cavalli e ai cavalieri, al tumulto e alla potenza che emanano, proprio perché eternamente solidificati, anch’essi immobilizzati -come le figure di Giacometti- nei volumi invisibili in cui sembrano inscritti.

[1] Occorre ricordare che Palazzo Abatellis e Castelvecchio non si devono soltanto al genio di Scarpa e alla rara lungimiranza di funzionari pubblici, ma anche a circostanze storiche. Negli anni ’50 del ‘900, molte città italiane si trovarono di fronte al problema della ricostruzione di quanto distrutto dai bombardamenti della seconda guerra mondiale, dando luogo a una sorta di nobile gara per ricostruire non solo edifici e monumenti, ma anche le identità collettive che in quei monumenti si rispecchiavano.

Fu una stagione straordinaria che vide Franco Albini chiamato a Genova per Palazzo Bianco, i BBPR all’opera con il Castello Sforzesco di Milano, e lo stesso Carlo Scarpa a Palermo e poi a Verona.

…………………………………………………………………………………………….

![]()

site & exhibition

We have seen Palazzo Abatellis (clip 05) and Castelvecchio (clip 07), where Carlo Scarpa, with masterful conservation interventions of buildings semi-destroyed by the war has created works that bring together -every time in a unrepetable unicum– history, architecture and staging exhibition.[1]

And we have seen, in the courts of Castelgrande and Maschio Angioino (clip 08), in borrowed and untouchable places, how certain characteristics of them could be used as components in the staging.

Let us now examine three other cases.

1.

The Castello di Rivoli (9.1), not far from Turin, has been too many times built, destroyed and rebuilt over the centuries. Savoy residence, barracks, even casino. It has been the object of a hundred projects over time -also by Filippo Juvarra in 1700-, and has seen the beginning of sumptuous reconstruction and completion works a hundred times, and their interruption as many times.

It was destroyed again and largely during the last war, and then again abandoned and dilapidated. Only at the end of the 1970s did the Regione Piemonte decided to restore it and make it the seat of the current Museum of Contemporary Art.

The project was entrusted to the architect Andrea Bruno.

In the site of the Castello di Rivoli we read that the choice -in my opinion, brilliant- was to keep the surviving testimonies giving importance to all the moments of the life of the Castle, starting from the interruption of the Juvarrian work, passing through the of late eighteenth century project by Carlo Randoni, until the interventions for the military. Andrea Bruno avoids making falsifications and completions, respecting the architecture, which becomes a real image of the history and the vicissitudes of the structure.

And here is that externally, as internally, stuccoes, frames and paintings have been preserved, damaged as by they were by the ravages of time and the neglect of men.

After that, from the opening to today, in forty years, even the staging of dozens of exhibitions has never made people feel the need to change anything substantial of the host place. From the initial collections of Arte Povera, the same rooms of the castle have magnificently housed contemporary authors and works of art, even completely different.

How is that possible? Just a quick reportage, just compare the same places and different artists to begin to understand what is happening (see for example 9.2/9.3/9.4 and also 9.5/9.6).

It goes without saying that physically walking around the rooms of the Castello di Rivoli is an experience that these notes can neither evoke nor even replace. But the images are perhaps enough to understand that everything is played on the lines of sight, that are -in this case- between the works and the context in which they are inserted, between the works and what remains of the Castle (9.7/9.8).

In Rivoli, contemporary art can triumph, can express all its revolutionary and vital power precisely because it stands out against the rubble of ancient aristocratic and bourgeois splendors.

The dark charm of the Castello di Rivoli, an aggregate of never finished, abandoned, dilapidated spaces, frozen in melancholic fragments, is the metaphor of the end of institutional beauty, of an idea of beauty that celebrates power.

Rivoli becomes -or represents- the death of that art. Become the fertile ground -background and matter- of the new art…

2.

The second case is paradoxically at the antipodes.

Looking at the Castello di Rivoli and Villa Borghese in Rome, we could talk about the power of seduction, but also about the problem, which is hidden in the imbalance, in the gap between the hosts and guests, between host place and the exhibitions hosted, between the material and the languages of the first and those of the exhibited works.

In the exhibition Giacometti. The sculpture at the Galleria Borghese in Rome, in the homonymous villa, in 2014, in a daring experiment, the tragic modernity of Giacometti, anti-monumental yet extraordinary, was compared with the great -and monumental- classical sculpture.

A courageous experiment -curated by Anna Coliva and Christian Klemm, with the staging by Daniela Ferretti- carried out proposing alignments, framing plays, comparisons between couples or groups of works, showing analogies and -above all- illuminating differences, as between the L’homme qui chavire and the David of Bernini (9.9), or between the hieratic Femme qui marche and the entire Egyptian room (9.10), also showing the estrangement, the excruciating loneliness, of the Homme qui marche in the entrance hall of the Gallery (9.12)…

It was an experiment that could open new paths for study and art criticism. All the more courageous in that it is not easy to compare in a single space works belonging to different centuries or millennia, as seen with the exhibition on Henry Moore at the Terme di Diocleziano, or in other exhibitions organized in various museums in Italy.

As usual, for the purposes of the reflections we are carrying out our attention does not go to the exhibition in general, but focuses on some parts and some aspects of its staging.

From a certain point of view, in fact, Giacometti at the Borghese Gallery report a problem.

The problem is that in Villa Borghese there is no rubble. The problem is that the Villa, with its amazing collection and its complete perfection, was and has always been for centuries the shameless celebration of Power: not only that of the Borghese family, of the Popes, of Imperial Rome, but the Power in absolute. Not coincidentally, almost all the palaces of Power, all over the world, wear -or try to flaunt- similar clothes.

We are -precisely- facing a scenario totally at the antipodes of the Castello di Rivoli.

In this scenario, the problem is that not only in the eyes of any visitor, like me, but also for the camera lens, the comparison was not between Giacometti and Bernini, or Canova, but between Giacometti and the whole sumptuous, fantastic, redundancy of the Gallery.

At the entrance, the strong direct light, the emptiness and the distance from the walls made the sculptures emerge from the relative penumbra of the rest of the hall (9.12). But elsewhere there was no way to find a frame that would give Giacometti breathing space. Maybe -who knows? – because it was impossible to move the pieces of the permanent collection, it seemed that Giacometti only had the remaining space left.And in the eyes of the visitor the sorrowful -and yet mighty- thinness of the modern man of Giacometti almost disappeared against the background of the decorations or in the doorways (9.11). He was lost in the visual noise of the Villa.

The problem, is, as I said, in the gap between the host place and the exhibitions hosted: between the history, the consistency, the material and the languages of the place and those of the exhibited works.

Let’s try to imagine another scenario.

Chase Manhattan Bank, New York (9.13), versus Villa Borghese (9.14).

The square, the skyscrapers, even the ‘inhabitants’ of Chase Manhattan Bank, in New York -which L’homme qui marche, Femme and Tête were destined for-, are totally anonymous, totally banal and interchangeable with a thousand others almost perfectly identical in all the business centers of the world.

And how can you think of Villa Borghese as an anonymous or banal space?

And now let’s imagine turning the game upside down once again.

If the comparison between Giacometti and Bernini had been set up in any art gallery of our cities, with bare white or grey walls, we are sure that, in front of L’homme qui marche by Giacometti the David, o the Apollo e Dafne by Bernini, would not have appeared as monumental -and a little ridiculous- marzipan works by a pop pastry chef?

Two remarks

The first. Finally, the doubt arises that at the Galleria Borghese the real heart of the exhibition was not Giacometti, but the comparison between some masterpieces of classical sculpture and those of a great contemporary sculptor. An exhibition, therefore, truly fascinating from a historical-critical point of view, not with one, but with two protagonists, or rather: two antagonists. The only problem -from our point of view- is that the classical sculpture played at home: and there was no match.

The second. At the end of these considerations, the problem, the importance and the charm of the design of the exhibition site emerge clearly, whether it is the result of the wisdom in the use and reuse of existing places or a daring ephemeral invention.

The theme of the invention of the exhibition site -which will be the focus of our attention in the next clips- can be introduced precisely with Scarpa and Giacometti.

We have said that it is not easy to make ancient and modern coexist and compare in a single space or in a single vision of space. But we cannot fail to think of the extraordinary legacy that Scarpa has left us, of his ability to approach the art of every age with the means, with the eyes and sensibility of modernity, in Castelvecchio, in Palazzo Abatellis, but also in many temporary exhibitions.

3.

In 1962, at the Venice Biennale, Scarpa set up the Giacometti room, which we can see in a beautiful photo by Ugo Mulas (9.15).

At a casual glance, it may seem like the neutral white space of an art gallery.

A careful look realizes that the walls are white, it is true, but they are fifths: they are aerial surfaces detached from the bottom and from each other. Two of them are just hinged by the slender frame of the drawings that turns the corner.

Scarpa also works by subtraction. He invented for Giacometti an extraordinary free, empty space, defined by the reciprocal order of immaterial surfaces. Matter is left to Giacometti’s sculptures, to bodies made of lacerated matter, immobile bodies or marching with all their energy, absorbed on the edge of a thought -as Giacometti himself in a snapshot of Cartier Bresson in Paris, the year before, (9.16), or that of Mulas during the staging phases in Venice (9.17)-.

Scarpa silently let the sculptures inhabit that space as if they were people, with their choreography, with the many framing plays, alignments, and intersections they suggested. He let them inhabit that space like the visitors who passed among them.

Just two more notes.

In Venice, as we saw in the Villa Borghese hall, Giacometti’s sculptures show that they need space, breath, but also -above all- to be together, as solitudes that need to be mirrored in each other (in fact, as expected in New York).

Inside the Italian Pavilion of the Biennale, Scarpa invents from scratch a space, a place for Giacometti and visitors to meet. But right there, in the living heart of contemporaneity, Scarpa paradoxically makes us think of the Battle of San Romano by Paolo Uccello (9.18), of the horses and riders, of the tumult and power they emanate, precisely because they are eternally solidified, also immobilized -like Giacometti’s figures- in the invisible volumes in which they seem inscribed.

[1] It should be remembered that Palazzo Abatellis and Castelvecchio are not only due to the genius of Scarpa and the rare foresight of public officials, but also to historical circumstances.

In the ’50s of the ‘900, many Italian cities were faced with the problem of the reconstruction of what was destroyed by the bombing of the Second World War, giving rise to a kind of noble race to rebuild not only buildings and monuments, but also the collective identities reflected in those monuments.

It was an extraordinary season that saw Franco Albini called to Genoa for Palazzo Bianco, the BBPR at work with the Castello Sforzesco in Milan, and the same Carlo Scarpa in Palermo and then in Verona.

9.1 Castello di Rivoli, veduta esterna dal piazzale

https://www.turismotorino.org/it/esperienze/cultura/Residenza%20Reale/castello-di-rivoli-museo-darte-contemporanea

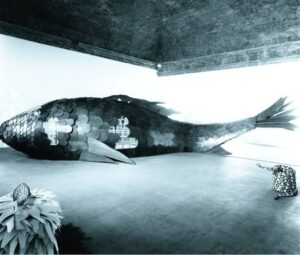

9.2 Frank O. Gehry, model of fish-building, a Rivoli, 1986 (n.b. stessa sala di 9.3 e 9.4)

https://www.castellodirivoli.org/en/mostra/frank-o-gery/

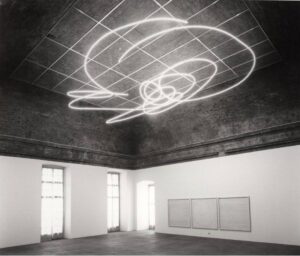

9.3 Lucio Fontana, La cultura dell’occhio, a Rivoli, 1986 (n.b. stessa sala di 9.2 e 9.4)

https://www.castellodirivoli.org/en/mostra/lucio-fontana-la-cultura-dellocchio/

9.4 (n.b. stessa sala di 9.2 e 9.3)

9.5 Maurizio Cattelan, Novecento, 1997 (n.b. stessa sala di 9.6)

https://www.turismotorino.org/it/esperienze/cultura/Residenza%20Reale/castello-di-rivoli-museo-darte-contemporanea

9.6 Emilio Vedova – Da dove… 1983-7, Da dove… !984-1, a Rivoli nel 1998

9.7 Paloma Varga Weisz, Root of a Dream, 2015

https://www.castellodirivoli.org/en/mostra/paloma-varga-weisz-root-of-a-dream/

9.8 Dennis Oppenheim, Between Drinks, 1991 a Rivoli nel 1998

…………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………….

9.9 mostra Giacometti. La scultura – Galleria Borghese, Roma

allestimento D. Ferretti, cura A. Coliva e C. Klemm

Giacometti, L’uomo che vacilla e Bernini, David

9.10 Donna che cammina

9.11

9.12 dettaglio del salone, L’homme qui marche e Femme (pensati insieme a Tête per Case Manhattan Plaza, New York)

9.13 Chase Manhattan Plaza, New York

http://www.alaintruong.com/archives/2020/10/22/38604199.html

9.14 Villa Borghese, Roma

https://it.wikipedia.org/wiki/Villa_Borghese#/media/File:Galleria_borghese_facade.jpg

…………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………….

9.15 Biennale di Venezia, 1962 – sala Giacometti

allestimento C. Scarpa

foto di Ugo Mulas

https://www.pinterest.it/pin/819795938390291499/visual-search/

9.16 Alberto Giacometti, Maeght Gallery, Parigi, 1961

foto di Henri Cartier-Bresson

http://taccuinodicasabella.blogspot.com/2012/07/lhomme-qui-marche-e-alberto-giacometti.html

https://www.henricartierbresson.org/en/expositions/henri-cartier-bresson-alberto-giacometti/

https://huxleyparlour.com/henri-cartier-bresson-on-alberto-giacometti/

9.17 Alberto Giacometti durante l’allestimento della sua sala alla Biennale ’62

foto Ugo Mulas

https://barbarapicci.com/2017/01/16/fotografia-ugo-mulas-2/

https://europost.eu/en/a/view/Tate-Modern-shows-Women-of-Venice

https://twitter.com/GuernseyJuliet/status/1166679702859333632/photo/2

9.18 Paolo Uccello, Battaglia di San Romano, Uffizi, Firenze