scenery flats, thresholds, lines of sight, Jabberwocky

la finestra sul lago di Le Corbusier, la Strada Novissima,

Palazzo Abatellis a Palermo

Prima di riprendere il tema sul percorso della mostra e sui rapporti tra percorso, opere e visitatori, occorre introdurre altre riflessioni e altri strumenti di lavoro.

Nel 1923-24 Le Corbusier (LC) costruisce una piccola casa per i suoi anziani genitori, sulle rive del lago Lemano, non lontano da Losanna.

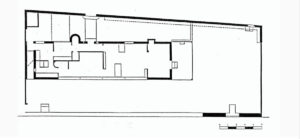

La casa, un gioiellino di 60 mq, è in un piccolo appezzamento di terreno, stretto tra la strada e il lago, e chiuso da un muro di confine lungo quasi tutto il perimetro (5.1).

Quasi tutto il perimetro. A sud, infatti, il muro non c’è, evidentemente per liberare l’affaccio verso il lago e le Alpi. Ma sul margine orientale di questo stesso fronte LC decide di alzare ancora una porzione di muro, e di ritagliarvi una finestra.

Perché non lascia aperto tutto il fronte sul lago? Perché ancora pochi metri di muro? E perché una finestra a due o tre metri dalla fine del muro, dalla pienezza del panorama? (5.2, 5.3)

A ben vedere -ma meglio sarebbe andare sul luogo-, non è difficile comprendere le ragioni, anzi: la precisa funzione, che LC affida a questa finestra.

Semplicemente, questa finestra invita chiunque entri in giardino a fermarsi sulla sua soglia, a sedersi intorno al tavolo e guardare. Gli permette di ‘agire’ sul paesaggio, sceglierne e separarne gli elementi -l’acqua, la montagna, le nuvole, il cielo-: decidere cosa inquadrare, cosa vedere oltre la finestra e cosa escludere dalla vista (5.4).

Ed è un invito irresistibile: nel web sono presenti decine di fotografie scattate da visitatori che si sono messi lì, ad aspettare fino a quando la finestra ha inquadrato una barca, un vela, un motoscafo, o una boa, o chissà che.

Da questo piccolo e geniale progetto d’architettura di LC si possono trarre alcuni insegnamenti, alcuni dei principali strumenti di lavoro -o artifici- nella progettazione del percorso di una mostra. Non è poi così strano. Ne abbiamo già parlato e ne parleremo ancora. Architettura e allestimento espositivo -che spesso si scambiano i ruoli- hanno alla fine lo stesso obiettivo: il progetto dell’esperienza che il visitatore farà di un luogo, nel primo caso, e degli oggetti esposti, nel secondo.

Come si può definire quella finestra?

È stata chiamata l’occhio sul lago: correttamente, poiché guida e condiziona lo sguardo. Ma se fermiamo per un attimo la nostra attenzione alla struttura che la include e che la disegna, ossia al muro, forse potremmo dire che questo muro è una quinta, come quelle dei teatri -quella chei francesi chiamano coulisse– , e la finestra è come il buco di una serratura. Le quinte servono a stabilire i limiti, i confini tra quello che vogliamo e quello che non vogliamo far vedere, i buchi della serratura, come ogni altra limitazione, servono a stimolare le nostre curiosità.

Il primo insegnamento che viene dalla finestra è dunque questo: le quinte agiscono per sottrazione, disegnano confini che sottraggono alcune componenti dal quadro complessivo per isolarne -metterne in evidenza, cioè mostrarne– altre.

Agendo per sottrazione, perciò selezionando, isolando, chiudendo in una cornice soltanto una parte del paesaggio, proprio con questo artificio possono offrire una chiave di lettura per comprendere pienamente la totalità del paesaggio.

D’altra parte, ripensandoci, quasi sempre arriviamo a comprendere la complessità di una cosa soltanto attraverso una sua piccola parte, oppure, all’inverso, possiamo comprendere una parte partendo dal tutto che la contiene: è un artificio del pensiero -e del linguaggio, della comunicazione- che gli studiosi e la retorica classica chiamano metonimìa o sineddoche.

E’ un artificio che l’uomo usa da sempre, quasi inseparabile dall’abduzione, la forma di ragionamento che ha reso leggendario Sherlock Holmes. Ecco allora l’investigatore che da pochi indizi ricostruisce la scena di un crimine. Il cacciatore che da poche tracce comprende i movimenti della preda. Gli storici che trovano fonti, testimonianze, reperti per proporre una lettura di un avvenimento (mentre altri storici ricorrono ad altre fonti, testimonianze, reperti per confutare quella lettura).

Analogamente, anche in una mostra d’arte o in un museo archeologico, sono quasi sempre relativamente pochi i pezzi -scelti ad hoc- con i quali viene rappresentata la personalità di un artista o un’intera civiltà antica…

Il secondo insegnamento è implicito nel primo.

Già a monte, prima di una mostra, la scelta dei pezzi, l’atto di decidere quali includere e quali escludere, definisce l’impostazione della mostra. E’ un atto tutt’altro che imparziale. Nell’allestimento, poi, proporre un punto di vista significa trascurarne altri: mettere in luce alcuni aspetti di un oggetto esposto inevitabilmente ne dà un’interpretazione, ma il prezzo è mettere in ombra altri aspetti.

L’insegnamento è questo, è che la mostra permette un rapporto diretto tra visitatore e oggetti esposti, ma non è -e non può mai essere- neutrale.

Torniamo alle quinte. Lo scopo esplicito del loro uso è il coinvolgimento del visitatore: sarà lui, con i suoi movimenti e con i suoi tempi, a scegliere ‘liberamente’ -in modo consapevole, oppure no- come inquadrare quanto si trova oltre la quinta, ad allargare o restringere, progressivamente e selettivamente, il quadro d’insieme.

Le virgolette dell’avverbio ‘liberamente’ sono dovute: come abbiamo visto, la libertà del visitatore è condizionata, il copione è già scritto e il visitatore può solo interpretarlo -e giudicarlo-.

Il condizionamento infatti è già nella predisposizione delle quinte, o, più precisamente, degli allineamenti tra visitatore, quinte e oggetti esposti. Questi allineamenti -ma il termine più preciso è traguardi- sono sempre presenti lungo il percorso di una mostra. Non è possibile evitarli. Il problema -il nostro compito- è invece usarli.

Nella nostra riflessione entrano due parole: soglia e traguardo. Cerchiamo di comprenderne meglio il significato.

La parola italiana traguardo, come ci ricordano i dizionari, prima di tutto designa l’atto o il risultato del traguardare. Quando il cacciatore prende la mira con un fucile, traguardare è l’atto con il quale allinea il suo occhio, la tacca, il mirino e il bersaglio -la preda-.

Quasi per proprietà transitiva, traguardo, poi, è anche il bersaglio, la preda, il punto d’arrivo -non solo quello di una gara-.

Per estensione, infine, il traguardo è anche l’atto di inquadrare o l’inquadratura stessa -dunque una selezione di quanto è visibile- che mette in relazione quanto è in primo piano con quanto appare in secondo piano, o sullo sfondo.

A ben vedere, dunque, il traguardo -l’atto del traguardare-, dunque, è un atto che lega tra loro cacciatore e preda, il vedere e l’essere visto. Il visitatore di una mostra e determinati oggetti mostrati.

La soglia è il passaggio obbligato attraverso il quale si supera un limite, un confine. Ad esempio, è la porta di una casa, o l’ingresso di una mostra, o di una sala, o, appunto, il bordo di una finestra in un muro.

Un esempio sontuoso di soglie nella loro declinazione più semplice lo dava la Strada Novissima, allestita nelle tre navate delle Corderie, per la Biennale di Architettura di Venezia del 1980 (5.5, 5.6).

Qui, Portoghesi, Cellini e D’Amato chiesero agli architetti invitati di disegnarsi da sé le facciate dietro le quali sarebbero stati presentati i loro lavori.

Nell’intenzione dei curatori, dunque, ogni facciata doveva essere non soltanto un ingresso, ma una sorta di manifesto della visione dell’architettura propria del suo autore. Così, nella Strada Novissima le facciate, come copertine di libri o come imagines agentes in un teatro della memoria, tentavano di sedurre i passanti evocando quanto nascosto alle loro spalle.

Ma una soglia può avere funzioni più complesse: come vedremo, lungo un percorso attentamente definito in ogni sua parte, la predisposizione e l’uso di una soglia o, meglio, di una successione di soglie, contribuisce a guidare silenziosamente i passi, la visione, tutta l’esperienza del visitatore.

Dove c’è una soglia -un varco, come la finestra sul lago o l’ingresso di una sala-, inesorabilmente c’è un traguardo, ci sono cose che da quel punto si vedono, oltre quel varco, e cose nascoste.

Ma per il progettista il discorso è inverso: se vuole un traguardo -un’inquadratura, uno sfondo-, allora deve usare -o se non c’è, inventare- una soglia, e un percorso che la attraversa.

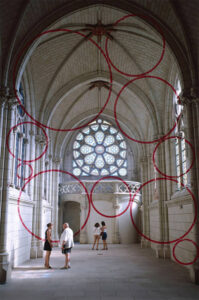

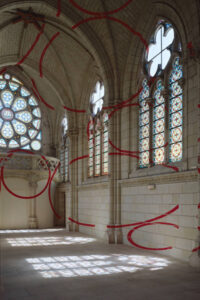

Tutto questo discorso di soglie e traguardi sembra molto complicato, ma diventa chiarissimo nelle intriganti opere dello svizzero Felice Varini, ad esempio in una installazione dichiaratamente didattica, It’s a point of view (5.7, 5.8) o in Encerclement à dix, realizzata nella Chapelle Jeanne d’Arc nel 1999, dove un’illusione prospettica e la sua decostruzione dipendono soltanto dalla posizione in cui si pone l’osservatore (5.9, 5.10).

Varini crea installazioni artistiche, lavori sulla percezione visiva: comunque operazioni che potremmo definire autoreferenziali e che si collocano e si richiudono nel rapporto tra luogo e osservatore.

Nelle mostre, invece, il gioco di soglie e traguardi non è mai autoreferenziale. Anzi, al contrario, è uno strumento essenziale che non serve soltanto a guidare i movimenti e l’attenzione del visitatore, e a predisporre le condizioni per il massimo godimento delle opere d’arte, ma si usa anche per costruire contesti e prospettive, per scandire e tenere insieme i tempi e i luoghi del percorso, in una nuova e diversa forma di punteggiatura.

Un dettaglio di Palazzo Abatellis, a Palermo, può far comprendere compiutamente il ruolo di soglie e traguardi nella regia del percorso espositivo.

Occorre qui limitarsi al dettaglio, benché ben altro studio meriterebbero il restauro di Palazzo Abatellis e il suo allestimento a sede museale. Realizzato tra il 1953 e il 1954, è uno dei capolavori di Carlo Scarpa, grande maestro dell’architettura e dell’allestimento espositivo.

Nelle sale 3, 4, 5 (5.12), Scarpa dispone soglie e traguardi per indicare le opere principali, -isolandole e mettendole in evidenza- e per usare queste stesse opere come termine di riferimento per tutte le altre.

Colloca dunque il busto di Eleonora d’Aragona di Francesco Laurana in una saletta d’angolo (5.12, sala 4, asterisco rosso), lungo il percorso tra due porte. Così facendo, nella sala 3 guida i passi del visitatore, offrendogli nel traguardo della porta un’anticipazione di quanto lo aspetta: crea una suspense, un’attesa, e lo attira nella sala 4 (5.13).

Nella sala 4, gli consente di vedere il busto da vicino, senza interferenze, e gli propone -o impone?- anche visioni da più lati (5.14, 5.15). Scarpa fa vedere al visitatore che una scultura non è un quadro, che non è sufficiente guardarla frontalmente, che occorre girargli intorno.

Aiuta il visitatore giocando sullo ‘stacco’ tra primo piano e sfondo: alle spalle del candido busto monta e fa girare sulle pareti un grande pannello verde, come un passepartout tridimensionale.

Poi, dopo essere stato attirato nella sala, il visitatore potrà prestare la propria attenzione alle altre opere presenti e confrontarle con il busto di Eleonora (5.16).

L’invenzione del passepartout come sfondo per dare risalto al candore della scultura viene riproposta anche per la testa di paggio attribuita ad Antonello Cagini (5.17), nella sala 5. Ma qui, con il fondo nero, le dimensioni ridotte e la cornice di legno, Scarpa suggerisce al visitatore una determinata ‘inquadratura’. Questa scelta non è in contraddizione con quanto predisposto per il busto di Eleonora: anche qui il visitatore può girare intorno alla scultura, ma girando trova un punto privilegiato per osservare la grazia di un dolcissimo profilo infantile.

Infine, uscendo dalla sala 4, sulla soglia della 5 il visitatore vede una statua che gli volge le spalle (5.12, asterisco azzurro).

Con un trucco diverso, ma anche qui, dunque, Scarpa lo invita ad entrare, ad andare avanti, ad oltrepassare la statua girandole intorno, a voltarsi indietro e a trovarsi di fronte -e inevitabilmente a confrontare tra loro- alcune opere incluse in un’unica inquadratura: la Madonna con il Bambino di Antonello Cagini, un bassorilievo e di nuovo, sullo sfondo, il busto di Eleonora nel traguardo tra le due sale (5.18).

In breve, Scarpa per mezzo dei traguardi guida il percorso e l’esperienza del visitatore, determina il luogo e lo spazio di ogni opera nelle sale del palazzo, lega le opere tra loro e ne propone confronti e gerarchie.

Con poche modifiche, lo stratagemma si ripete: il visitatore va avanti, gira intorno agli oggetti, poi si volta, torna indietro, e infine riprende il cammino. Il percorso perde ogni linearità, si adatta al carattere di opere e luoghi e condiziona i tempi e modi dell’attenzione.

Nelle prossime clip vedremo come soglie e traguardi possano trovare declinazioni diverse nelle diverse realtà proprie di ogni mostra, anche in strategie espositive differenti.

Ma, prima di procedere, occorre introdurre ancora una riflessione sull’esperienza che un visitatore fa degli oggetti in mostra.

Se riprendiamo l’ipotesi di un’analogia tra percorso della mostra e racconto (vedi clip 03), ci troviamo immediatamente di fronte a una difficoltà: il ‘racconto’ della mostra non si legge come in un libro, ma si vede e -a volte- si ascolta, quasi come a teatro.

Il racconto di una mostra è composto non di parole, ma di oggetti, di cose che accadono, di forme.

In un racconto così, senza parole, come si legano le cose tra loro? come si costruiscono le frasi, come si sviluppa una trama?

Le poesie metasemantiche di Fosco Maraini, quelle che lui chiamava fànfole, forse ci possono suggerire una risposta.

La fànfola più famosa comincia così:

Il lonfo non vaterca né gluisce

e molto raramente barigatta,

ma quando soffia il bego a bisce bisce

sdilenca un poco e gnagio s’archipatta.

[…]

Le fànfole sono composizioni di parole inventate, di suoni d’invenzione privi di significato. Ma qualsiasi lettore o ascoltatore, ammaliato da metrica, grammatica e sintassi all’apparenza ben riconoscibili -riconoscendo cioè soggetti, verbi e complementi-, o sedotto dall’assonanza e dal ricordo di parole vere, non può evitare di tentarne un’interpretazione, non può evitare di tentare di assumerle come proposizioni dotate di senso.

Visitando una mostra, il visitatore si trova molto spesso in una situazione non molto diversa dal lettore di fànfole. Tutti abbiamo bisogno di trovare il senso delle cose. Tutti riteniamo impossibile che le cose riunite in una mostra siano prive di una ragione che le tiene insieme.

Il problema è che le cose esposte in una mostra -siano esse opere d’arte, materiali, forme, eventi, oggetti naturali o prodotti dell’uomo- non hanno quasi mai un significato univoco ed evidente. Neanche per gli specialisti, figùrati per tutti gli altri.

D’altra parte, i testi scritti presenti in una mostra -didascalie, spieghe, spiegoni- non possono avere il respiro e l’articolazione di un libro e, spesso, nel breve tempo di una visita, non vengono neanche letti. (Un discorso a parte -che verrà affrontato in una delle prossime clip- meriterebbero le audioguide o, più in generale, tutti i supporti informativi digitali)

Ma non è questo il punto.

Il punto è il rapporto tra visitatore e oggetto esposto: un rapporto che è -e deve essere- concreto, diretto, fisico, senza altra mediazione che i propri sensi, poiché questa è l’esperienza che solamente la mostra può offrire.

Si tratta allora della possibilità di coinvolgere il visitatore di una mostra, più o meno consapevolmente, come il lettore di una fànfola. Si tratta di coinvolgerlo con la ‘grammatica’ e la ‘metrica’ delle assonanze, delle analogie e delle differenze tra le cose esposte davanti ai suoi occhi. Se egli può cogliere le assonanze di suoni, o le rime che ritornano tra i versi di una poesia, se può riconoscere leoni o fantastici vascelli volanti nelle nuvole che attraversano il cielo, allora può scoprire somiglianze, congruenze e ricorrenze tra forme, può piano piano arrivare a riconoscere cosa accomuna -e cosa distingue-, ad esempio, le sculture di Laurana e dei Cagini.

Allora, così come nelle fànfole sono necessarie una grammatica e una sintassi per legare tra loro suoni altrimenti insignificanti, nella mostra -in un racconto senza parole-, per legare tra loro cose esposte e visitatore è necessaria una ‘sintassi’ -o meglio una paratassi- che orienti la trama di rapporti e prospettive, di traguardi, di sfondi e riscontri.

Come ha fatto Scarpa a Palermo, a Palazzo Abatellis, e -forse più compiutamente, come vedremo- a Verona, a Castelvecchio.

…………………………………………………………………………………………….

![]()

scenery flats, thresholds, lines of sight, Jabberwocky

Before resuming the theme on the path of the exhibition and on the relationship between path, works and visitors, it is necessary to introduce other reflections and furher work tools.

In 1923-24 Le Corbusier (LC) built a small house for his elderly parents, on the shores of Lake Geneva, not far from Lausanne.

The house, a jewel of 60 sqm, is in a small plot of land, narrow between the road and the lake, and closed by a border wall along almost the entire perimeter (5.1).

Almost the entire perimeter. To the south, actually, there is no wall, evidently to free the view towards the lake and the Alps. But on the eastern edge of this front LC decides to raise again a portion of the wall, and cut a window.

Why not leave open the entire front of the lake? Why still a few meters of wall? And why a window two or three meters from the end of the wall, from the fullness of the landscape? (5.2, 5.3)

Looking carefully -but it would be better to go to the place-, it is not difficult to understand the reasons, indeed: the precise function, which LC assigns to this window.

Simply, this window invites anyone entering the garden to stop at its threshold, to sit around the table and look. It allows him to ‘act’ on the landscape, choose and separate the elements -the water, the mountain, the clouds, the sky-: decide what to frame, what to see beyond the window and what to exclude from view (5.4).

And it’s an irresistible invitation: on the web there are dozens of photographs taken by visitors who have been there, to wait until the window has framed a boat, a sail, a motorboat, or a buoy, or who knows what.

From this small and ingenious architectural project you can draw some lessons, some of the main tools -or artifice- in the design of the path of an exhibition. It’s not that weird.

We’ve talked about this, and we’ll talk about it again. Architecture and exhibition staging -which often exchange roles- have at the end the same objective: the project of the experience that the visitor will make of a place, in the first case, and the objects on display, in the second.

How can you define that window?

It has been called the eye on the lake: correctly, because it guides and conditions the look. If we stop for a moment our attention to the structure that includes it and that draws it, that is to the wall, maybe we could say that this wall is a flat, like those of the theaters -what the French call coulisse-, and the window is like a keyhole. The flats serve to establish the limits, the borders between what we want and what we don’t want show, the holes in the lock, like any other limitation, serve to stimulate our curiosity.

The first lesson that comes from the window is therefore this: the scenery flats act by subtraction, they draw borders that subtract some components from the overall picture to isolate -highlight, that is show– others components.

Acting by subtraction, therefore selecting, isolating, closing in a frame only a part of the landscape, just with this artifice the fifths can offer a key to fully understand the totality of the landscape.

On the other hand, on second thought, we almost always come to understand the complexity of a thing only through a small part of it, or, on the contrary, we come to understand a part starting from the whole that contains it: it is an artifice of thought -and of language, of communication- that classical rhetoric call metonymy or synecdoche.

It’s an artifice that man has always used, almost inseparable from abduction, the form of reasoning that made Shelock Holmes legendary. So here’s the investigator who reconstruct a crime scene from a few clues. The hunter who from few traces understands the movements of the prey. Historians who find sources, testimonies, to propose a reading of an event (while other historians resort to other sources, testimonies, to refute that reading).

Similarly, even in an art exhibition or in an archaeological museum, there are almost always relatively few pieces -chosen ad hoc– with which is represented the personality of an artist or an entire ancient civilization…

The second lesson is implicit in the first.

Already upstream, before an exhibition, the choice of pieces, the act of deciding which to include and which to exclude, defines the setting of the exhibition. It’s not an impartial act. In the exhibition staging, then, proposing a point of view means neglecting others: highlighting some aspects of an exposed object inevitably gives an interpretation, but the price is overshadowing other aspects.

The lessons is that the exhibition allows a direct relationship between the visitor and the exhibits, but it is not -and can never be- neutral.

Back to the flats. The explicit purpose of their use is the involvement of the visitor: it will be he the one who, with his movements and his times, to choose ‘freely’ -in a conscious way, or not- how frame what is beyond the flat, to open or close, progressively and selectively, the whole picture.

The inverted commas of the adverb ‘freely’ are due: as we have seen, the freedom of the visitor is conditioned, the script is already written and the visitor can only interpret and judges it.

The conditioning is in fact already in the predisposition of the flats, or, more precisely, of the alignments between visitor, flats and exposed objects. These lines of sight -but the most precise Italian term is traguardi– are always present along the path of an exhibition. They cannot be avoided. The problem -our task- is to use them instead.

Two words enter into our reflection: traguardo -line of sight- and threshold. Let us try to understand its meaning better.

The Italian word traguardo, as the dictionaries remind us, primarily is the act or the result of the traguardare (to make a line of sight). When the hunter aims with a rifle, traguardare is the act with which he align his eye, the notch, the viewfinder and the target -the prey-.

Almost by transitive property, the Italian word traguardo, then, is also the target, the prey, the point of arrival -not only that of a race-.

By extension, finally, the traguardo is also the act of framing or the framing itself -therefore a selection of what is visible- that relates what is in the foreground with what appears in the background.

On closer inspection, therefore, the traguardo -the act of make a line of sight- is therefore an act that binds hunter and prey, seeing and being seen. The visitor of an exhibition and certain exhibits.

Please note. Since we do not find an English word that maintains the same range of meanings as the Italian “traguardo”, depending on the context we will use different expressions such as: frame, framing, line of sight.

The threshold is the obligatory passage through which you go beyond a limit, a boundary. For example, the door of a house, or the entrance of an exhibition, or a room, or, indeed, the edge of a window in a wall.

A sumptuous example of thresholds in their simplest declination was given by the Strada Novissima, set up in the three naves of the Corderie (ancient rope factory, for the Venice Architecture Biennale in 1980 (5.5, 5.6).

Here, Portoghesi, Cellini and D’Amato asked the invited architects to draw themselves the facades behind which their works would be presented.

In the intention of the curators, therefore, each facade had to be not only an entrance, but a sort of manifesto of the vision of architecture proper to its author. Thus, in the Strada Novissima, the facades, like book covers or as imagines agentes in a theatre of memory, attempted to seduce passers by evoking what was hidden behind them.

But a threshold can have more complex functions: as we shall see, along a path carefully defined in each part, the predisposition and the use of a threshold or, better, of a succession of thresholds, helps to silently guide the steps, the vision, the whole experience of the visitor.

Where there is a threshold -a breach, like the window on the lake or the entrance of a hall-, inexorably there is a frame or a line of sight, there are things that you see from that point, through that breach, and hidden things.

But the designer thinks in reverse: if he wants a framing play -or a line of sight between foreground and background-, then he must use -or invent- a threshold, and a path that crosses it.

All this talk of thresholds and lines of sight seems very complicated, but it becomes very clear in the intriguing works of the Swiss Felice Varini, for example in an openly educational installation, It’s a point of view (5.7, 5.8) or in Encerclement à dix, realized in the Chapelle Jeanne d’Arc in 1999, where a perspective illusion and its deconstruction depend only on the position in which the observer is placed (5.9, 5.10).

Varini creates artistic installations, works on visual perception: however operations that we could define self-referential and that find meaning and close themselves in the relationship between place and observer.

In exhibitions the game of thresholds and frames is never self-referential. Indeed, on the contrary, it is an essential tool that serves not only to guide the movements and attention of the visitor, and to prepare the conditions for the maximum enjoyment of works of art, but it is also used to build contexts and perspectives, to mark and hold together the times and places of the path, in a new and different form of punctuation.

A detail of Palazzo Abatellis, in Palermo, can fully understand the role of the thresholds and the lines of sight -the play of backgrounds and alignments- in the design of the path of an exhibition.

Here it is necessary to limit oneself to the detail, though other study would deserve the restoration of Palazzo Abatellis and its set up as a museum. Designed between 1953 and 1954, it is one of the masterpieces of Carlo Scarpa, great master of architecture and exhibition staging.

In rooms 3, 4, 5 (5.12), Scarpa arrange thresholds and lines of sight to indicate the main works, -isolating and highlighting them- and to use these same works as a reference term for all the others.

He therefore places the bust of Eleonora d’Aragona by Francesco Laurana in a corner room (5.12, room 4, red asterisk), along the path between two doors. In this way, in room 3 he guides the steps of the visitor, offering him an anticipation of what awaits him through the frame of the door: he creates a suspense, a wait, and attracts him into room 4 (5.13).

In room 4, it allows him to see the bust closely, without interference, and proposes -or imposes? – even visions from multiple sides (5.14, 5.15). Scarpa shows the visitor that a sculpture is not a painting, that it is not enough to look at it frontally, that it is necessary to turn around it.

He help the visitor by playing on the ‘detachment’ between the foreground and the background: behind the white bust he mounts and turns on the walls a large green panel, like a three-dimensional passepartout.

Then, after being lured into the room, the visitor can pay attention to the other works present and compare them with the bust of Eleonora (5.16).

The invention of the passepartout as a background to emphasize the candour of the sculpture is also proposed for the page head attributed to Antonello Cagini (5.17), in room 5. But here, with the black background, the small size and the wooden frame, Scarpa suggests to the visitor a determined point of view. This choice is not in contradiction with what is prepared for the bust of Eleonora: here too the visitor can turn around the sculpture, but turning finds a privileged point to observe the grace of a sweet child profile.

Finally, leaving room 4, on the threshold of 5, the visitor sees a statue that turns its back (5.12, blue asterisk).

With a different trick, but also here, Scarpa invites him to enter, to go forward, to go beyond the statue turning around, to turn backwards and to be faced -and inevitably to compare each other- some works included in a single frame: The Madonna and Child by Antonello Cagini, a bas-relief, and again, in the background, the bust of Eleonora closed in the line of sight between the two halls (5.18).

In short, Scarpa guides the visitor’s journey and experience by the lines of sight, determines the place and space of each work in the halls of the palace, ties the works together and proposes comparisons and hierarchies.

With few modifications, the stratagem repeats itself: the visitor goes forward, turns around the objects, then turns, goes back, and finally resumes the journey. The path loses all linearity, adapts to the character of works and places and conditions the times and modes of attention.

In the next clips we will see how thresholds and lines of sight can find different declinations in the different realities of each exhibition, even in different exhibition strategies.

But, before proceeding, it is necessary to introduce another reflection on the experience that a visitor makes of the objects in the exhibition.

If we take up the hypothesis of an analogy between the exhibition and the story (see clip 03), we are immediately faced with a difficulty: the ‘tale of the exhibition’ is not read as in a book, but can be seen and -sometimes- listened, almost like at the theater.

The story of an exhibition is composed not of words, but of objects, of things that happen, of forms.

In a story like this, without words, how do you tie things together? How do you build phrases, how do you develop a plot?

Jabberwocky [1], the famous poem by Lewi Carroll, and the metasemantic poems of Fosco Maraini, what he called fànfole, perhaps can suggest an answer.

Twas brillig, and the slithy toves

Did gyre and gimble in the wabe;

All mimsy were the borogoves,

And the mome raths outgrabe.

[…]

Jabberwocky and the fànfole are compositions of invented words, of inventive sounds devoid of meaning. But any reader or listener, bewitched by metrics, grammar and syntax apparently well recognizable -that is recognizing subjects, verbs and complements-, or seduced by the assonance and the memory of true words, cannot avoid attempting an interpretation, cannot avoid trying to take them as propositions with meaning.[

By visiting an exhibition, any visitor is often in a situation not very different from the Jabberwocky or the fànfole reader. We all need to make sense of things. We all consider it impossible that things collected in an exhibition are devoid of a reason that holds them together.

The problem is that the things exhibited in an exhibition -works of art, or materials, forms, events, natural objects or products of man- hardly ever have an unambiguous and evident meaning. Not even for specialists, think of all the others.

On the other hand, the written texts present in an exhibition -captions, explanations, large explanations- cannot have the breath and articulation of a book and, often, in the short time of a visit, are not even read. (A separate reflection -which will be addressed in one of the next pills- would deserve audioguides or, more generally, all digital information media)

But that’s not the point.

The point is the relationship between the visitor and the exposed things: a relationship that is -and must be- concrete, direct, physical, without other mediation than his senses, since this is the experience that only the exhibition can offer.

It is then the possibility of involving the visitor of an exhibition, more or less consciously, as the reader of Jabberwocky. It is a matter of involving him with the ‘grammar’ and the ‘metric’ of assonances, with the similarities and differences between the things exposed before his eyes.

If he can grasp the assonances of sounds, or the rhymes that return between the verses of a poem, if he can recognize lions or fantastic flying vessels in the clouds that cross the sky, then he can discover similarities, congruences and recurrences between forms, he can gradually come to recognize what unites -and what distinguishes-, for example, the sculptures of Laurana and Cagini.

Then, just as in Jabberwocky and in the fànfole a grammar and syntax are needed to bind together otherwise insignificant sounds, in the exhibition -in a tale without words-, to hold together exposed things and visitor is necessary a ‘syntax’ – or better a ‘parataxis’- that orients the plot of relationships and perspectives, frames, backgrounds and feedback.

As Scarpa did in Palermo, in Palazzo Abatellis, and -perhaps more fully, as we shall see- in Verona, in Castelvecchio.

Jabberwocky, published in 1871 in the novel Through the looking-Glass, and What Alice Found There,

is probably the poem that inspired the fànfole, the metasemantic poems, by Fosco Maraini, which, in fact, replicate its compositional structure adapting it to the Italian lexicon and grammar.

5.1 Villa le Lac, Le Corbusier 1923-24 – modello

https://en.wikiarquitectura.com/building/villa-le-lac/#imagen-3d-4

5.2 pianta

5.3 la finestra sul lago

https://www.museums.ch/org/it/Villa–Le-Lac–de-le-Corbusier

5.4 il traguardo – foto Arnaud Philippe (?)

https://www.proviaggiarchitettura.com/proviaggi_eventi/le-corbusier/

………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………

5.5 Arsenale di Venezia, le Corderie

https://venezia.italiani.it/corderie-arsenale/

5.6 Mostra Internazionale di Architettura, 1980, la Strada Novissima alle Corderie

https://www.area-arch.it/dentro-la-strada-novissima/

https://www.architettilombardia.com/pagine/maxxi.asp

https://www.phaidon.com/agenda/architecture/articles/2018/june/29/when-the-venice-biennale-went-pomo/

………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………

5.7 Felice Varini, It’s a point of view

http://glou.over-blog.com/article-it-s-a-point-of-view-54504057.html

5.8 la decostruzione, da un altro ‘punto di vista’

5.9 Felice Varini, Encerclement à dix, Chapelle Jeanne d’Arc/Centre d’Art Contemporain, Thouars, France 1999

https://www.gwarlingo.com/2012/optical-illusions-of-felice-varini/ courtesy http://varini.org

5.10 idem

………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………

5.11 Carlo Scarpa, Palazzo Abatellis, Palermo, 1953-54, la corte

https://turismo.comune.palermo.it/palermo-welcome-luogo-dettaglio.php?tp=68&det=21&id=177

5.12 pianta del piano terreno

(asterisco rosso: busto di Eleonora d’Aragona – asterisco blu: Madonna con Bambino)

5.13 traguardo dalla sala 3 alla 4

5.14 sala 4, Francesco Laurana, busto di Eleonora d’Aragona

5.15 vista frontale

foto di Nicola Lo Calzo (?)

https://iris.unipa.it/retrieve/handle/10447/287575/565291/ok%20ok%20Giunta%20Casa%20Vogue.pdf

5.16 l’altro lato della sala 4

5.17 Antonello Cagini (attr.), testa di paggio

5.18 traguardo dalla sala 5 alla 4

https://www.italianways.com/it/palazzo-abatellis-e-lazzurro-del-cielo/ (?)