tracciati, successione temporale, simultaneità

paths – first notions: traces, temporal succession, simultaneity

Quando si parla di mostre e musei, oggetto delle nostre riflessioni, la nozione di percorso, in sé, è elementare: per percorso si intende genericamente l’itinerario più o meno obbligato che curatore e allestitore predispongono per il visitatore.

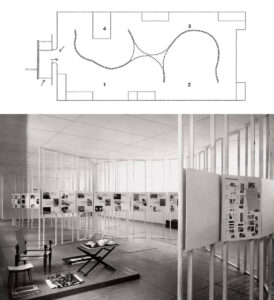

Nei disegni di elaborazione e di presentazione del progetto di un allestimento, il percorso del visitatore viene rappresentato molto spesso -forse più per abitudine che per convenzione- con una combinazione di frecce e linee -continue o tratteggiate- che attraversano i luoghi di una mappa.

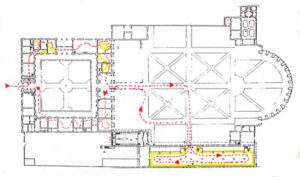

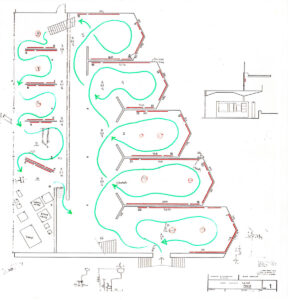

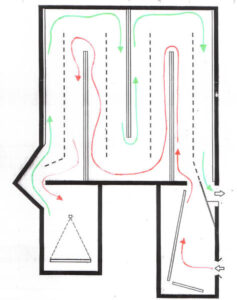

E’ il caso, ad esempio, delle tavole di studio di tre progetti di mostre di architettura: Alvar Aalto 1898/1986, a Palazzo Te, Mantova 1998(1.1), Ignazio Gardella – progetti e architetture 1933/1990, al Padiglione d’Arte Contemporanea (PAC), Milano 1992,(1.2), James Stirling – i musei, alla Galleria Comunale d’Arte Moderna, Bologna 1990 (1.3).

Queste tavole di studio sono programmaticamente schematiche: nascono per i briefing di lavoro come supporto alla riflessione o alla discussione intorno al percorso, o -alla fine del progetto- come loro sintetica registrazione. Mettono in fila i passi, ma lasciano ancora all’immaginazione e alla parola la descrizione dell’esperienza reale predisposta per il visitatore.

Tuttavia, già nella loro schematicità queste piante consentono di osservare alcune caratteristiche fondamentali del percorso e della mostra.

Prima di tutto, possiamo osservare che la linea del percorso evidentemente si adatta agli spazi che attraversa, ma disegna idealmente un anello che quasi sempre si apre e si chiude sulla soglia che segna l’ingresso e l’uscita della mostra. Ed è là, intorno a quella soglia, accanto alla biglietteria, che non casualmente possono trovare posto anche il bookshop, il guardaroba e in generale tutti i servizi relativi all’accoglienza.

La prima qualità che il disegno del percorso rivela è questa: la mostra è un luogo chiuso, separato dal resto del mondo.

E’ -lo ripeto- un qualità fondamentale, una conditio sine qua non.

Le ragioni della inevitabilità, della necessità, di questa chiusura sono tante, e non soltanto legate alla sicurezza di cose o persone.

Qui, per ora, è sufficiente segnalare che i musei e le mostre fanno parte di quella categoria di luoghi straordinari che Foucault definiva eterotopie, o, altrove, dispositivi.

La mostra è, in estrema sintesi, un’eterotopia poiché contesta ogni altro spazio reale, e lo fa creando uno spazio tanto perfetto, meticoloso e ordinato, quanto il nostro -quello della nostra realtà d’ogni giorno- è disordinato, mal organizzato e caotico.

L’istituzione mostra è un dispositivo in quanto prescrive i comportamenti distinti -ma congiunti- di curatore e allestitore e, non solo attraverso l’operato di questi, il comportamento del visitatore.[1]

Il suo costituirsi come eterotopia e dispositivo, il suo essere un luogo -un giardino incantato- separato dal mondo ordinario e dotato di prerogative sue proprie, conferisce alla mostra, ad esempio, il potere di trasformare ufficialmente un orinatoio in un’opera d’arte, come ben sapeva Duchamp già nel 1917.

La facoltà di selezionare oculatamente cose o eventi, di staccarli dai luoghi loro consueti, di straniarli, permette infatti alla mostra di inserirli in nuovi ordini, nuove visioni, nuovi contesti, a volte persino sorprendenti per il visitatore.

La seconda caratteristica della mostra e del suo percorso emerge dal confronto di quelle tavole di studio con un altro -e famoso- disegno: una tavola di progetto di Louis Kahn per il piano del traffico di Filadelfia, del 1952 (1.4).

Anche qui le frecce compongono tracciati lineari per rappresentare un movimento. Ma, mentre nelle mostre -come abbiamo visto- i tracciati disegnano un sistema sostanzialmente chiuso, ad anello, qui i tracciati si sommano o si dividono per collegare quartieri, città, territorio, mondo, in un sistema complessivo aperto.

La differenza più importante, implicita nella prima, è però un’altra.

Le linee disegnate da Kahn congiungono punti. Vanno da un punto a un altro punto, cercando di ridurre ogni attrito, ogni intoppo. La misura della qualità dei percorsi è puramente quantitativa: è la velocità. Tra il punto di inizio e il punto di arrivo non vi sono luoghi intermedi, vi è soltanto il tempo, inteso come fastidio dell’attesa. Per questo è perfettamente corretta l’idealizzazione di Kahn: il disegno può serenamente cancellare i luoghi, eliminare ogni materia della città e mostrare solo i tracciati.

Nel percorso della mostra, al contrario, l’inizio e la fine sono soltanto margini, confini. La mostra è tutto quello che accade tra quei due punti, quello che accade in mezzo, durante il viaggio.

Parafrasando le parole di Mies van der Rohe a proposito delle grandi esposizioni, le mostre hanno significato e ragion d’essere soltanto quando sono in grado di dar luogo all’intensificazione della vita. Oppure, potremmo anche dire, quando sono in grado di concentrare l’esperienza del visitatore sul tema che propongono, rimuovendo per la breve durata della visita tutto il resto del mondo.

Ogni momento del percorso di una mostra deve essere in grado di sedurre il visitatore, e deve essere progettato come il teatro della sua esperienza [2]. Il progetto della mostra è il progetto dell’esperienza che ne farà il visitatore.

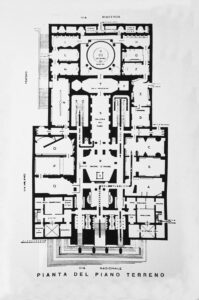

In altri disegni di studio, il percorso di una mostra appare rappresentato segnalando la successione degli spazi con numeri o con lettere (1.5, 1.6).

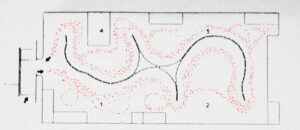

La sostanza non cambia: il percorso è comunque collegato all’idea di una disposizione di cose o eventi esposti secondo una sequenza lineare, e si richiude ad anello in prossimità dell’ingresso della mostra. Ma se nel disegno di Max Bill integriamo i numeri con le tracce di immaginari visitatori (1.7), diventa evidente un altro aspetto fondamentale del percorso già presente nelle prime due piante: un vincolo con il quale il progetto di un percorso deve misurarsi.

Nel disegno di Max Bill, non soltanto l’idea di un percorso lineare sembra sia all’origine della disposizione dei pannelli espositivi, ma -anche e soprattutto- appare evidente che i passi del visitatore di fronte ai pannelli vanno sempre da sinistra a destra, e all’interno dei vari spazi, coerentemente, descrivono anelli in senso orario. Non diversamente da quanto appare nelle tavole di studio che abbiamo visto prima (1.2).

Non è casuale. Molto semplicemente, nel mondo occidentale scriviamo e leggiamo da sinistra a destra. Percorsi rovesciati, da destra a sinistra o in senso antiorario, risultano per noi innaturali, faticosi, discontinui.

D’altra parte, come vedremo in seguito, proprio per queste loro controindicazioni -il moto ‘a rovescio’, ‘di andata e ritorno’, a scatti in avanti per poi suggerire di guardare indietro, etc.-, possono essere usati come artifici narrativi, per intervenire sul comportamento del visitatore.

L’idea di un’analogia tra gli andamenti lineari della scrittura-lettura e del percorso, tuttavia, appare soltanto parzialmente rappresentativa di quello cha accade realmente in una mostra.

Certo, i passi di un visitatore, come i suoni delle parole che pronunciamo o leggiamo, si dispongono uno dopo l’altro, inesorabilmente lungo la linea del tempo.

Ma noi non vediamo ‘una cosa dopo l’altra’: in ogni istante abbracciamo con lo sguardo un quadro d’insieme -una sorta di panorama- in cui molte e diverse cose si presentano simultaneamente.

De Saussure segnalava chiaramente questa differenza. Gli elementi dei significanti auditivi, affermava, si dispongono uno dopo l’altro; formano una catena. Tale carattere appare immediatamente non appena li si rappresenti con la scrittura e si sostituisca la linea spaziale dei segni con la successione nel tempo.

Al contrario, i significanti visivi […] possono offrire complicazioni silmultanee su più dimensioni [3].

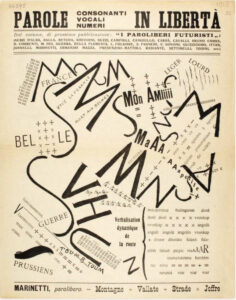

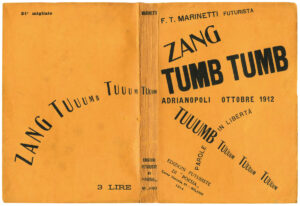

Un esempio lampante ed elementare di questa differenza è offerto dalle tavole parolibere dei futuristi (1.8, 1.9). Al primo sguardo, si coglie l’immagine nel suo insieme, come un quadro. E poi vediamo e leggiamo le singole parole.

La composizione tipografica delle parole stampate ne complica -come dice De Saussure- il significato. E di converso il significato -e il suono, anche se solo letto mentalmente- delle parole complica il senso e la struttura della composizione, del quadro d’insieme.

La simultaneità dei due significanti visivi -testi e grafica-, e dei due linguaggi, ne altera, espande e integra i rispettivi significati.

Nei disegni di progetto di un allestimento, la linea con cui rappresentiamo astrattamente il percorso definisce una successione temporale.

Ma nella realtà della mostra -dove il tempo è scandito dai passi del visitatore e dalla successione degli spazi, delle sale che attraversa-, ad ogni passo, davanti agli occhi del visitatore si presentano, agiscono simultaneamente e interagiscono tra loro più sistemi significanti, più linguaggi -i diversi linguaggi delle cose esposte, dei testi scritti, della grafica, dell’allestimento, dell’architettura, etc.-.

Nella realtà, la sequenza temporale appare nuovamente quando, ad ogni passo, ciò che abbiamo davanti a noi si compone con la memoria di quanto abbiamo già visto, e, ancora, quando il nostro sguardo intravede da lontano e ci guida verso ciò che verrà.

Da tutto questo emergono due nuovi aspetti fondamentali dell’allestimento e del percorso della mostra.

Il primo. L’allestimento di una mostra non ha un proprio linguaggio. Seleziona, organizza e fa interagire tra loro più linguaggi. E’ in grado di ibridarli e di intervenire sulle loro espressioni. L’allestimento è un metalinguaggio.

Il secondo. Nella visita della mostra, lungo il percorso, successione temporale e simultaneità, sviluppo diacronico e visione sincronica, sono inscindibili e sempre presenti. Ma non sono affatto continui: anzi, ad ogni passo del visitatore tutto può cambiare. Come vedremo, è proprio orchestrando le modalità e gli accenti del loro inevitabile intreccio che prende forma la struttura narrativa della mostra [4].

[1] Sui concetti di eterotopia e di dispositivo cfr. anche rispettivamente i saggi Il viaggio e Istituzioni, il dispositivo mostra, in questo sito, nella sezione Riflessioni. Nelle note dei saggi è riportata anche la relativa bibliografia.

[2] Su questi temi cfr. anche il saggio Il viaggio, in questo sito, nella sezione Riflessioni.

[3] F. De Saussure, Corso di linguistica generale, Laterza, Bari 2008, pag. 88, Cours de linguistique générale – Edition critique, Editions Payot & Riveges, Paris, 1997, pag. 103.

[4] Su galleria e rotonda, cfr. anche il saggio Scenari del mostrare, in questo sito, nella sezione Riflessioni

…………………………………………………………………………………………….

![]()

paths – first notions

traces, temporal succession, simultaneity

When we talk about exhibitions and museums, the subject of our reflections, the notion of a path, in itself, is elementary: by path we generally mean the more or less obligatory itinerary that the curator and staging designer prepares for the visitor.

In the elaboration and presentation drawings of the staging, the visitor’s path is very often represented -perhaps more by habit than by convention- with a combination of arrows and lines -continuous or dashed – that go through the places on a map.

This is the case, for example, of the study tables of three architectural exhibition plans: Alvar Aalto 1898/1986, at Palazzo Te, Mantua 1998 (1.1), Ignazio Gardella – progetti e architetture 1933/1990, at the Padiglione d’Arte Contemporanea (PAC), Milan 1992, (1.2), James Stirling – the museums, at the Galleria Comunale d’Arte Moderna, Bologna 1990 (1.3).

These study tables are programmatically schematic: they are created for work briefings as a support for reflection or discussion around the path, or -after the project is finished- as their synthetic recording. They line up the steps, but still leave the description of the real experience prepared for the visitor to the imagination and to the word.

However, already in their schematic form these plans allow us to observe some fundamental characteristics of the path and of the exhibition.

First of all, we can observe that the line of the path obviously adapts to the spaces it crosses. But this line ideally draws a ring that almost always opens and closes on the threshold that marks the entrance and exit of the exhibition. And it is there, around that threshold, next to the ticket office, that it is not accidental that the bookshop, the cloakroom and in general all the reception services can also find a place.

The first quality that the drawing of the path reveals is this: the exhibition is a closed place, separated from the rest of the world.

It is -I repeat- a fundamental quality, it is a conditio sine qua non.

There are many reasons that justify the inevitability, the necessity, of this closure, and they are not only related to the safety of things or people.

Here, for now, it is sufficient to point out that museums and exhibitions are part of that category of extraordinary places that Foucault defined as heterotopias (hétérotopies), or, elsewhere, devices (dispositifs).

The exhibition is, in a nutshell, a ‘heterotopia’ since it questions every other real space, and it does so by creating a space that is as perfect, meticulous and orderly as ours space -that of our everyday reality- is messy, badly organized and chaotic.

The exhibition institution is a ‘device’ in that it prescribes the distinct -but joint – behaviors of curator and staging designer and, not only through their work, the behavior of the visitor. [1]

Its constitution as a ‘heterotopy’ and ‘device’, its being a place -an enchanted garden- separated from the ordinary world and endowed with its own prerogatives, gives the exhibition, for example, the power to officially transform a urinal into a work of art, as Duchamp knew as early as 1917.

The faculty of carefully selecting things or events, of detaching them from their usual places, of alienating them, allows the exhibition to insert them into new orders, new visions, new contexts, sometimes even surprising for the visitor.

The second characteristic of the exhibition and its path emerges from the comparison of those study tables with another -and famous- drawing: a design table by Louis I. Kahn for the Philadelphia Traffic Plan, from 1952 (1.4).

Here, too, the arrows compose linear paths to represent a movement. But, while in the exhibitions -as we have seen- the layouts draw a substantially closed system, in a ring, here the layouts are added or divided to connect neighborhoods, cities, territories, world, in an overall open system.

The most important difference, implicit in the first, however is another.

The lines drawn by Kahn connect points. They go from one point to another point, trying to reduce any friction, any hitch. The measure of the quality of the routes is purely quantitative: it is the speed. Between the starting point and the arrival point there are no intermediate places, there is only time, understood as the annoyance of waiting. This is why Kahn’s idealization is perfectly correct: drawing can serenely erase places, eliminate all matter of the city and show only the paths.

In the path of the exhibition, on the contrary, the beginning and the end are only margins, borders. The exhibition is everything that happens between those two points, what happens in between, during the journey.

Paraphrasing the words of Mies van der Rohe about the exhibitions, the exhibitions have meaning and raison d’etre only when they are able to give rise to the intensification of life. Or, we could also say, when they are able to concentrate the visitor’s experience on the theme they propose, removing the rest of the world for the short duration of the visit.

Every moment of the journey of an exhibition must be able to seduce the visitor, and must be designed as the theater of his experience [2]. The exhibition design is the design of the experience that the visitor will make of it.

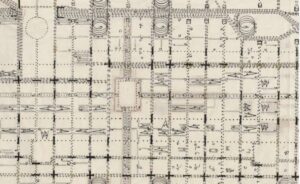

In other study drawings, the path of an exhibition appears represented by indicating the succession of spaces with numbers or letters (1.5, 1.6).

The substance does not change: the path is however connected to the idea of an arrangement of things or events displayed in a linear sequence, and closes in a ring near the entrance to the exhibition. But if in Max Bill’s drawing we integrate the numbers with the traces of imaginary visitors (1.7), another fundamental aspect of the path already present in the first two plans becomes evident: a constraint with which the design of a path must be measured.

In Max Bill’s drawing, not only the idea of a linear path seems to be at the origin of the layout of the exhibition panels, but -also and above all- it is evident that the steps of the visitor in front of the panels always go from left to right, and within each space, coherently, they describe clockwise rings. Not unlike what appears in the study tables we have seen earlier (1.2).

It is not accidental.

Quite simply, in the Western world we write and read from left to right. Inverted paths, from right to left or counterclockwise, are unnatural, tiring, discontinuous for us.

However, as we will see later, precisely because of these contraindications, the ‘backward’ motion -or ‘back and forth’, moving forward and then suggesting to look back, etc.- can be used as narrative artifices, to intervene on the visitor’s behavior.

The idea of an analogy between the linear trends of writing-reading and the path, however, appears only partially representative of what actually happens in an exhibition.

Of course, the steps of a visitor, like the sounds of the words we speak or read, are arranged one after the other, inexorably along the time line.

But we do not see ‘one thing after another’: in every moment we embrace an overall picture -a sort of panorama- in which many and different things occur simultaneously.

De Saussure clearly pointed out this difference. The elements of the auditory signifiers, he said, are arranged one after the other; form a chain. This character appears immediately as soon as you represent them with writing and replace the spatial line of the signs with the succession in time.On the contrary, visual signifiers […] can offer silmultaneous complications on multiple dimensions. [3]

A glaring and elementary example of this difference is offered by the tavole parolibere (‘free word tables’) of the Italian Futurists (1.8, 1.9). At first glance, we see the image as a whole, like a picture. And then we see and read the individual words.

The typographical composition of the printed words complicates -as De Saussure says- its meaning. Conversely, the meaning -and the sound, even if only mentally read- of the words complicates the sense and the structure of the composition, of the overall picture.

The simultaneity of the two visual signifiers -texts and graphics-, and of the two languages, alters, expands and integrates their respective meanings.

In the design drawings of the staging, the line with which we represent the path abstractly defines a temporal succession.

But in the reality of the exhibition -where time is marked by the steps of the visitor and by the succession of spaces, of the rooms that hi crosses-, at each step, before the eyes of the visitor more significant systems, more languages -the different languages of the exposed things, of the texts, graphics, layout, architecture, etc.- are presented, act simultaneously and interact with each other.

In reality, the temporal sequence appears again when, at every step, what we have before us is composed with the memory of what we have already seen, and, again, when our gaze glimpses from afar and guides us towards what will come.

From all this emerge two new fundamental aspects of the exhibition staging and path.

The first one. The staging of an exhibition does not have its own language. It selects, organizes and interacts more languages with each other. It’s able to hybridize them and intervene in their expressions. The staging of an exhibition is a metalanguage.

The second. In the visit of the exhibition, along the way, temporal succession and simultaneity, diachronic development and synchronic vision, are inseparable and always present. But they are not continuous at all: on the contrary, at every step of the visitor everything can change.

As we shall see, it is precisely by orchestrating the modes and accents of their inevitable interweaving that the narrative structure of the exhibition takes shape [4].

[1] About the concepts of heterotopy and device cf. also respectively the essays Il viaggio and Istituzioni, il dispositivo mostra, in this site, in the section Riflessioni. The notes to the essays also contain the relevant bibliography.

[2] About these themes cf. also the essay Il viaggio, in this site, in the section Riflessioni.

[3] F. De Saussure, Corso di linguistica generale, Laterza, Bari 2008, pag. 88, Cours de linguistique générale – Edition critique, Editions Payot & Riveges, Paris, 1997, pag. 103.

[4] About gallery and roundabout , cf. also the essay Scenari del mostrare, in this site, in the section Riflessioni

1.1 A,Castiglioni e N.Marras, Alvar Aalto 1898/1986, Palazzo Te, Mantova 1998 – pianta generale del percorso

http://nicolamarras.eu/portfolio/alvar-aalto-18981976/

1.2 A.Castiglioni e N.Marras, Ignazio Gardella – progetti e architetture 1933/1990, Padiglione d’Arte Contemporanea (PAC), Milano 1992 – pianta del percorso

http://nicolamarras.eu/portfolio/ignazio-gardella-progetti-e-architetture/

1.3 A.Castiglioni e N.Marras, James Stirling – i musei, Galleria Comunale d’Arte Moderna, Bologna 1990

http://nicolamarras.eu/portfolio/i-musei-di-james-stirling-michael-wilford-associates/

1.4 Louis I. Khan, Plan of Proposed Traffic Movement Pattern, Philadelphia, 1952

https://www.architectmagazine.com/aia-architect/aiaknowledge/philadelphia-almost_o

https://www.domusweb.it/it/progettisti/louis-isadore-kahn.html

https://drawingmatter.org/drawing-movement-and-medium-michael-webb-in-conversation-with-mark-dorrian-episode-2/

https://www.facebook.com/louiskahnarchitect/photos/1930341163869481

1.5 Max Bill, Die Gute Form, al Swiss Werkbund, Basilea 1949

https://wornandwound.com/art-time-max-bill-die-gute-form/

https://www.flickr.com/photos/146095643@N07/37776372865

1.6 Dino Alfieri, Mario de Rienzi e altri, Mostra della Rivoluzione Fascista, Palazzo delle Esposizioni, Roma, 1932-34

1.7 Max Bill, Die Gute Form, immaginarie tracce di visitatori

1.8 Filippo Tommaso Marinetti, Parole in libertà, 1915

https://amouthfulofpennies.wordpress.com/2016/08/12/a-meal-for-memory/parole-in-liberta/

https://fondazionecirulli.org/artwork/parole-in-liberta/

1.9 Filippo Tommaso Marinetti, Parole in libertà, 1915

https://amouthfulofpennies.wordpress.com/2016/08/12/a-meal-for-memory/parole-in-liberta/

https://fondazionecirulli.org/artwork/parole-in-liberta/